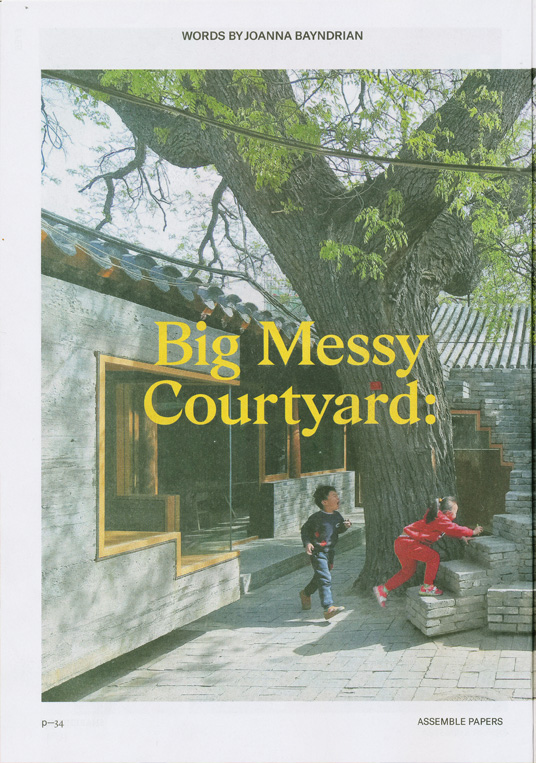

Big Messy Courtyard: Micro Yuan’er

01 June 2018

Joanna Bayndrian

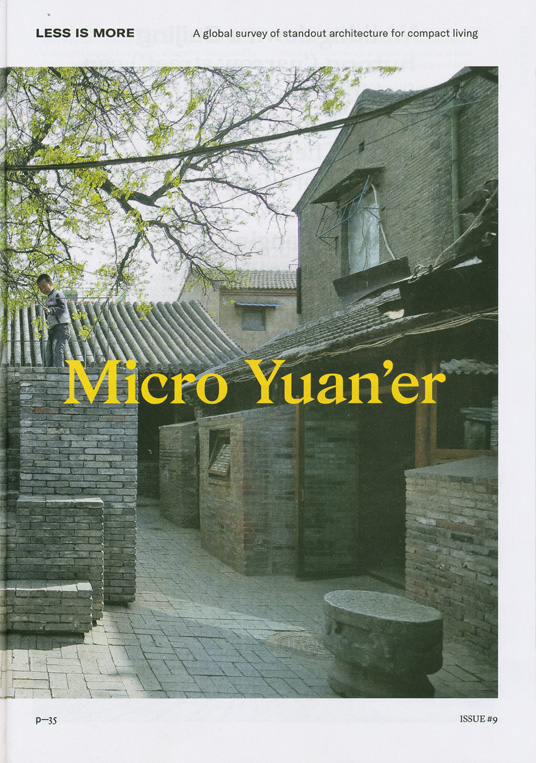

Walking down a Beijing hutong (‘narrow street’) can feel like you’ve stumbled into a big, slightly chaotic, family home. There are always people hanging around, street furniture arranged for conversations, washing hanging out to dry, bikes scattered about.

Beijing’s old low-rise neighbourhoods, made up of narrow alleyways and courtyard houses, bring a vital human scale to the capital’s cityscape, otherwise dominated by dense apartment blocks, imposing government buildings and ‘starchitecture’. But there are serious challenges to bringing ageing housing infrastructure into the 21st century, especially in a city fast approaching 22 million people, where whole neighbourhoods are transitioning from public to semi-public, semi-private to private, sometimes at breakneck speed.

The personality and energy of Beijing’s hutong areas is deeply embedded in how they have evolved over centuries, and continue to be reinvented. They are living organisms, experiments in multi-layered histories and informal architectures. Many of the changes to traditional courtyard dwellings, such as subdivisions and add-ons, can be traced back to the post-1949 collectivisation of Beijing’s housing stock, giving siheyuan, or ‘courtyard house’, another name in Beijing vernacular: dazayuan, which literally translates to ‘big messy courtyard’. The city’s culture of flux has changed hutong streetscapes irreversibly, yet the emphasis on social interactivity is, in a way, sympathetic to the character of the original structures, which were built for multi-generational living.

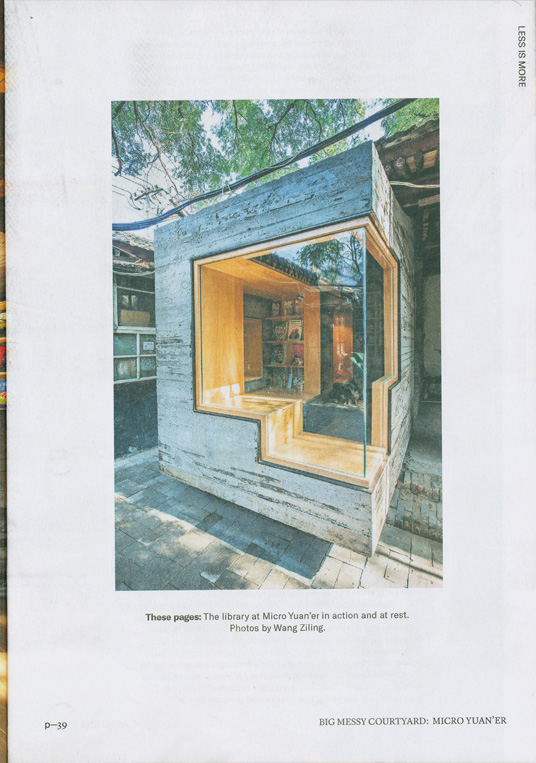

It’s been two years since Zhang Ke, founder of ZAO/standardarchitecture, unveiled the pilot project Micro Yuan’er Children’s Library and Art Centre inside a modest 145 square metre dazayuan at 8 Cha’er Hutong, Dashilar, a popular hutong area situated just south of Tiananmen Square.

A graduate of Tsinghua and Harvard universities, Zhang’s human-centric architectural practice has received a number of international accolades since he started the studio in 2001 (most recently, the prestigious Alvar Aalto Medal in 2017). Micro Yuan’er is one of a number of ZAO/standardarchitecture’s self-initiated hutong renewal projects in Beijing. In an interview via WeChat, Zhang reflects: “I think one of the most interesting facts of the Micro Yuan’er is [that] no designers wanted to take on the challenge, because there were quite a few families still living inside. The government thinks this situation is very difficult for renewal. But we felt from the very beginning that this co-living situation is what could make the project more typical, in the overall old city-wide scenario.”

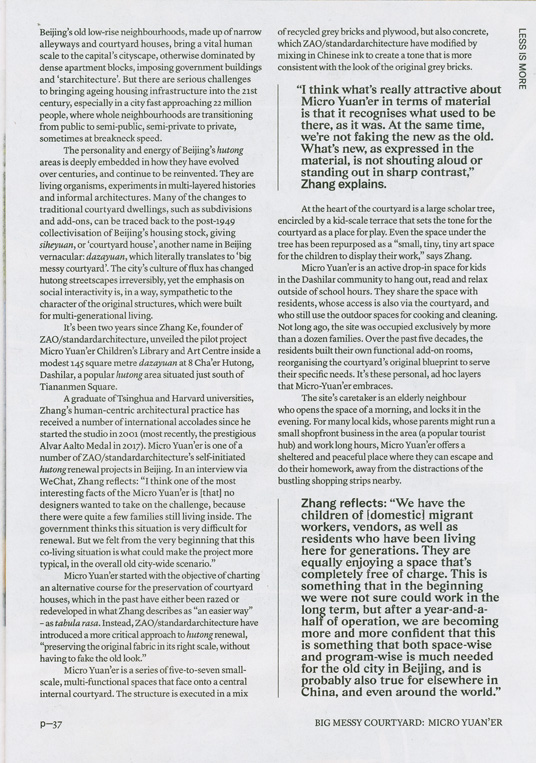

Micro Yuan’er started with the objective of charting an alternative course for the preservation of courtyard houses, which in the past have either been razed or redeveloped in what Zhang describes as “an easier way” – as tabula rasa. Instead, ZAO/standardarchitecture have introduced a more critical approach to hutong renewal, “preserving the original fabric in its right scale, without having to fake the old look.”

Micro Yuan’er is a series of five-to-seven small-scale, multi-functional spaces that face onto a central internal courtyard. The structure is executed in a mix of recycled grey bricks and plywood, but also concrete, which ZAO/standardarchitecture have modified by mixing in Chinese ink to create a tone that is more consistent with the look of the original grey bricks.

“I think what’s really attractive about Micro Yuan’er in terms of material is that it recognises what used to be there, as it was. At the same time, we’re not faking the new as the old. What’s new, as expressed in the material, is not shouting aloud or standing out in sharp contrast,” Zhang explains.

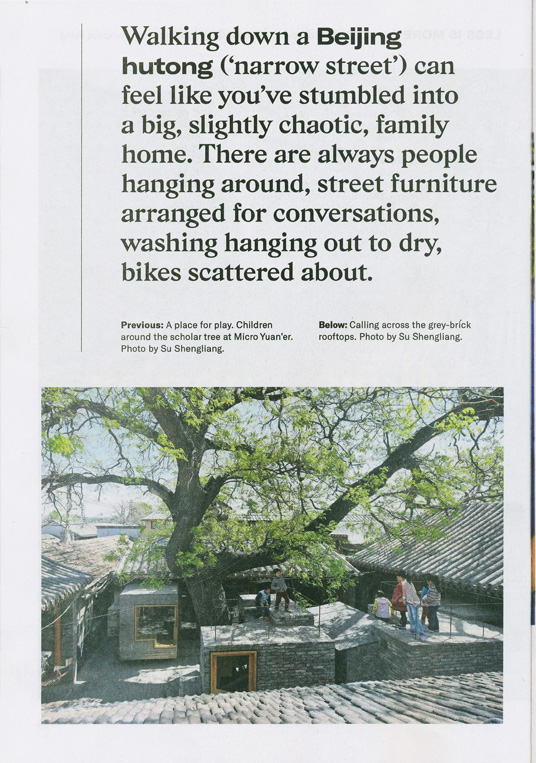

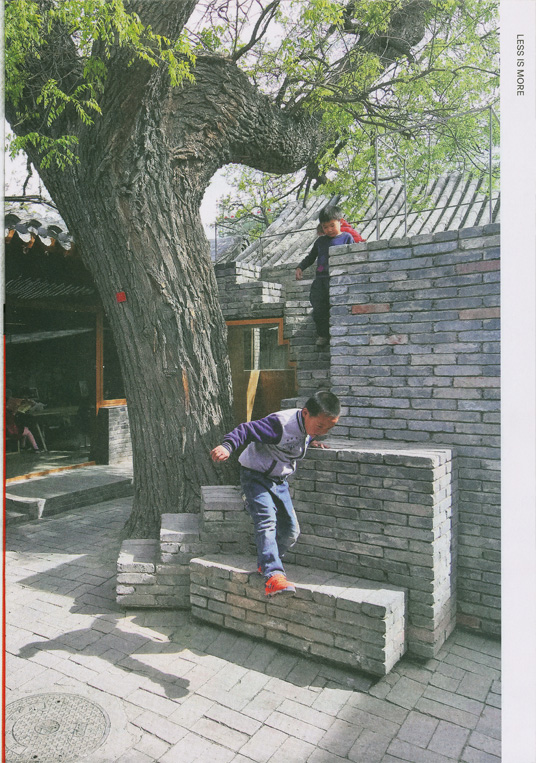

At the heart of the courtyard is a large scholar tree, encircled by a kid-scale terrace that sets the tone for the courtyard as a place for play. Even the space under the tree has been repurposed as a “small, tiny, tiny art space for the children to display their work,” says Zhang.

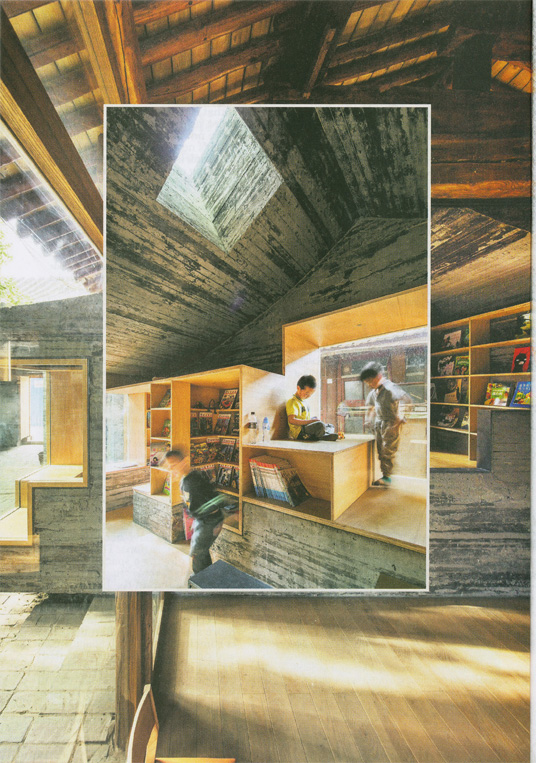

Micro Yuan’er is an active drop-in space for kids in the Dashilar community to hang out, read and relax outside of school hours. They share the space with residents, whose access is also via the courtyard, and who still use the outdoor spaces for cooking and cleaning. Not long ago, the site was occupied exclusively by more than a dozen families. Over the past five decades, the residents built their own functional add-on rooms, reorganising the courtyard’s original blueprint to serve their specific needs. It’s these personal, ad hoc layers that Micro-Yuan’er embraces.

The site’s caretaker is an elderly neighbour who opens the space of a morning, and locks it in the evening. For many local kids, whose parents might run a small shopfront business in the area (a popular tourist hub) and work long hours, Micro Yuan’er offers a sheltered and peaceful place where they can escape and do their homework, away from the distractions of the bustling shopping strips nearby.

Zhang reflects: “We have the children of [domestic] migrant workers, vendors, as well as residents who have been living here for generations. They are equally enjoying a space that’s completely free of charge. This is something that in the beginning we were not sure could work in the long term, but after a year-and-a-half of operation, we are becoming more and more confident that this is something that both space-wise and program-wise is much needed for the old city in Beijing, and is probably also true for elsewhere in China, and even around the world.”

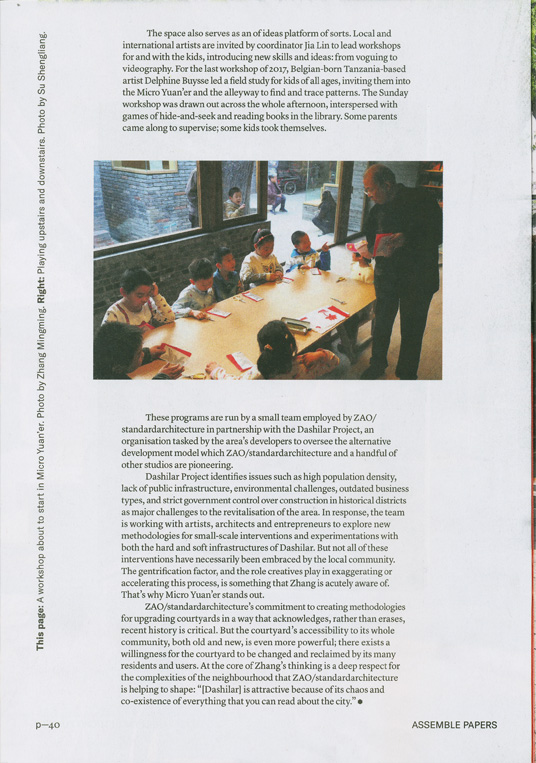

The space also serves as an of ideas platform of sorts. Local and international artists are invited by coordinator Jia Lin to lead workshops for and with the kids, introducing new skills and ideas: from voguing to videography. For the last workshop of 2017, Belgian-born Tanzania-based artist Delphine Buysse led a field study for kids of all ages, inviting them into the Micro Yuan’er and the alleyway to find and trace patterns. The Sunday workshop was drawn out across the whole afternoon, interspersed with games of hide-and-seek and reading books in the library. Some parents came along to supervise; some kids took themselves.

These programs are run by a small team employed by ZAO/standardarchitecture in partnership with the Dashilar Project, an organisation tasked by the area’s developers to oversee the alternative development model which ZAO/standardarchitecture and a handful of other studios are pioneering.

Dashilar Project identifies issues such as high population density, lack of public infrastructure, environmental challenges, outdated business types, and strict government control over construction in historical districts as major challenges to the revitalisation of the area. In response, the team is working with artists, architects and entrepreneurs to explore new methodologies for small-scale interventions and experimentations with both the hard and soft infrastructures of Dashilar. But not all of these interventions have necessarily been embraced by the local community. The gentrification factor, and the role creatives play in exaggerating or accelerating this process, is something that Zhang is acutely aware of. That’s why Micro Yuan’er stands out.

ZAO/standardarchitecture’s commitment to creating methodologies for upgrading courtyards in a way that acknowledges, rather than erases, recent history is critical. But the courtyard’s accessibility to its whole community, both old and new, is even more powerful; there exists a willingness for the courtyard to be changed and reclaimed by its many residents and users. At the core of Zhang’s thinking is a deep respect for the complexities of the neighbourhood that ZAO/standardarchitecture is helping to shape: “[Dashilar] is attractive because of its chaos and co-existence of everything that you can read about the city.”

"What is a family? Is it just a genetic chain, parents and offspring, people like me? Or is it a social construct, an economic unit, optimal for child rearing and divisions of labor? Or is it something else entirely: a store of shared memories, say? An ambit of love? A reach across the void? I could list various possibilities. But I'd never arrived at a definite answer..."

- Barack obama, dreams from my father

As feminists, we at Assemble Papers spend a lot of time thinking about the enabling and constricting structures of family. These structures are given physical shape in our built environment, which we create, as the 1980s feminist architect group The Matrix wrote, "in accordance with a set of ideas about how society works, who does what and who goes where."

We build the city in the image of the society we assume. The design of suburbia rests on the assumption of a self-sufficient nuclear family and a stay-at-home mother. On the other hand, childcare centres, kindergartens, nursing homes, communal living, shared laundries, chore wheels, playgrounds -this is the infrastructure that liberates women and makes caring a collective effort.

As Australian cities accept apartments in ever greater numbers, we thought it was time to query our assumptions about ‘who goes where'. Living closer to each other suggests a tighter, more elegant puzzle - of ages, of relationships, of interdependencies. We did not foresee that, as we were commencing our research, we would suddenly be asked to cast a vote on other people's families. Though ugly, demeaning and unnecessary, the Australian postal survey on marriage equality painted rainbows on shopfronts and drew us into conversations we had not had before. And it brought us legal recognition of same-sex marriage, an implied recognition that family, one of the most fundamental human organisational systems, is also one of the most fluid and changeable.

Deeply informed by this event, this issue of Assemble Papers became a celebration of difference, and of the courage and imagination that underpins every chosen family.

Resources can be pooled. Caring work can be re-divided. Children can be given pride of place in public space. A diverse city is a more imaginative city. And an architecture of openness is a better architecture.

Radical Families

words by naomi stead

Sporadic but timely ideas, essays, reviews and opinions on cities and contemporary culture, from the hyper-local to the internationally relevant

ʻRadicalʼ is a relative term. One person's wildly avant-garde is another person's solidly conventional. And in my observation, the more you venture into radical territory, or surround yourself with radical folk, the more you realise your own squareness, your own commitment to orthodoxies: what used to seem progressive becomes commonplace, what was daring becomes tame, what was queer becomes ordinary. Such are the processes of normalisation, and such processes calcify in architectural form.

So, what then is a radical family, and where does it live? Some would say a queer family is radical, but what's a queer family these days? If you abandon norms, or actively reject them, then the shackles are off, and radical families can range from post-punk socialist collectives, to fluid polyamorous entanglements, to joyful gaggles of Chosen Family, and so on it goes. When ʻfamilyʼ is unshackled from ʻnatureʼ and ʻbiologyʼ, and hitched instead to ʻchoiceʼ or ʻartificeʼ or even just to ‘loveʼ, then the possibilities are endless. To my eye, the real limitation comes from the conventionalism of the stock of available dwellings, more than it does from the myriad of possible social arrangements.

The general rule, in modern Australia, is that only one family will occupy a given dwelling, and this immediate, biological, heterosexual, nuclear family unit will live in isolation from their friends and extended families and - more importantly - from the families that they might choose. There is a certain obligatory normality built in; I am obliged to conform to my house. This is partly a function of administrative oversight: the landlord obliges the tenant to be normal, as does the plumber, the electricity provider, the insurance company, the bank, the local government rubbish-collection regime. But the dwelling itself also has a normalising effect: the rooms, their size and number and partitioning, their arrangement and furnishing and appointment.

But then again, what about families like mine? What if it's simply two adults and their child, living alone together, in an ordinary house, with ordinary rooms and an ordinary garden and an ordinary landlord and ordinary contents insurance, and trouble with the downstairs outside light, and magnets on the fridge, and tiny sharp bits of Lego on the floor, waiting to be stepped on barefoot?

So far, so heteronormative, I hear you say. It's just the same old nuclear family, reproducing the same old patterns, it just happens that the parents are both women; it's a regular family which just happens to be coloured rainbow. Move on, nothing radical to be seen here, you say. And that is true! Except when it's not.

Because for some people in the world, a rainbow family is very much not normal, and very much not desirable. And when you're part of such a queer grouping, you never know when that person might show up at your door: the person for whom you represent an actual existential threat to the sanctity of family, the moral and physical safety of children, and hence the very foundations of society. And then there they are: come to fix the dishwasher, and ask what your husband does, whereupon you are obliged to come out (unless you don't, having weighed the situation in a second, and decided to lie).

One ʻcomes outʼ as a queer family, in different ways and for different reasons and after having come out as an individual. In fact, the coming-out process becomes more pronounced and more pointed -people who thought they were safe to assume you were straight because of the presence of the child are wrong-footed and mortified, people who simply can't imagine how it would be physically possible are dumbfounded. Coming out is, in any case, a lifelong endeavour. It doesn't happen once and grandly and then not again: it happens every day, and with a banal, endless repetition that becomes very decidedly ordinary.

It might start with parents, sisters, brothers, stepsisters, aunts and uncles and grandparents, but over time it continues - and by necessity, not exhibitionism. At various times it becomes administratively unavoidable to come out to the woman at the bank, to teachers, to plumbers, to colleagues, to real estate agents, to landlords, to builders, to tradies, to locksmiths, to doctors, to nurses, to midwives, to HR staff, to administrators, to staff in the electricity-provider call centre, to internet network installers, to census collectors, charity organisations, to people in the playground, to teachers, to schoolmates, to lecturers, to colleagues, to bosses. To strangers. And to whomever reads articles like this one. For myself, the only person I've never had to come out to is my son - since he knew from the beginning.

Does the coming-out process get easier? Yes it does. Does it get boring and tiresome? Sure as hell. Is there ever a time when. it's completely easy, when there is no worry at all, not even a twinge of wariness about how this information will be received and how the other person will react to this particular member of this not-particularly radical family? No, that time has never come - or not yet, or not yet for me.

So: the entanglements of a dwelling, or its location within a larger regulatory and financial and administrative and governmental system, obliges queer families to come out. But more than this, such a dwelling nudges its occupants towards normality- to fit within norms. The question becomes, then, what happens when our radical family types, our queer domestic arrangements, are not accommodated by the spaces we find ourselves living (disorientedly) within? What happens to domestic space when some of us set out to queer the family further, to invent unique kinship groups with whom we choose to live in varying degrees of intimacy and proximity?

The dwellings of such radical families might both express and envelop queer affiliation, in all its kaleidoscopic forms, its dimensions and nuances of attachment, its very queerness in the sense of its strangeness, its one-off, unique, tailored specificity to a group of people and the intentional family they have formed. I'd like to see that.