Beijing, la poesia degli hutong

08 December 2016

There is a growing trend in the Chinese capital to try to bring back to life historic districts with their typical, low-rise houses designed around a courtyard. Here are two of the most interesting projects, by Zhang Ke

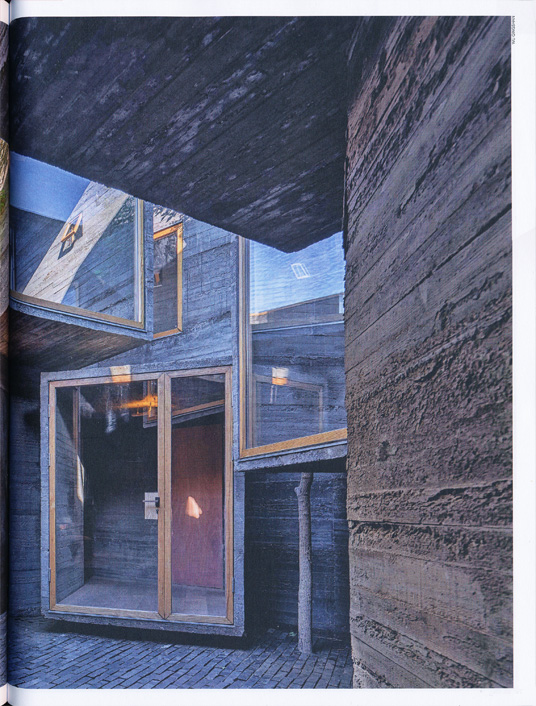

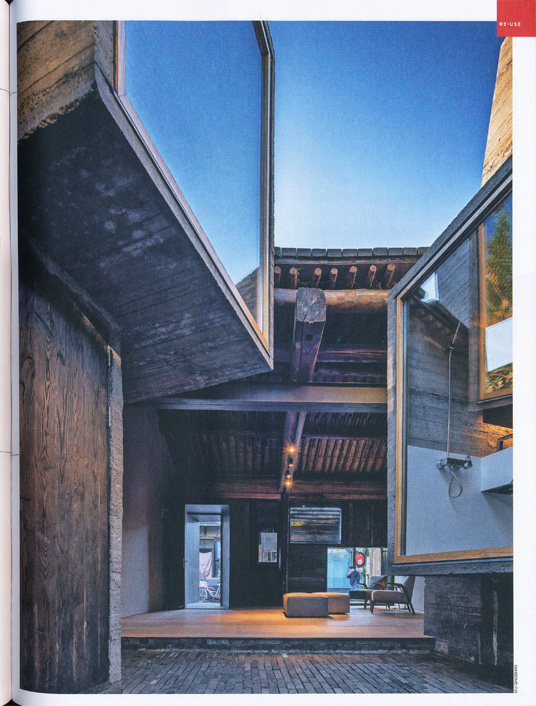

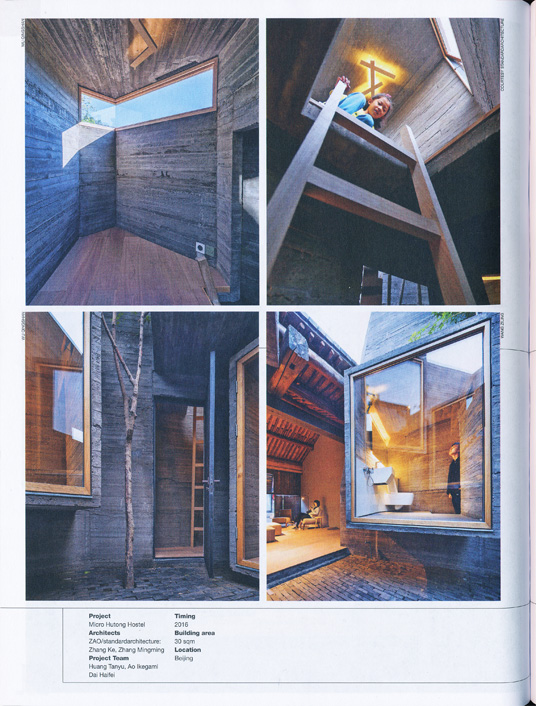

Preserve, protect, enhance. After years of frenzied building schemes that led to the demolition of many of the historic districts around the Forbidden City, Beijing has changed direction, abruptly halting these processes and introducing a new and no less drastic policy. "In the past, a notice would go up on a wall, the bulldozers would come in and a whole district would be torn down to make way for new tower blocks," explains Nicola Saladino, an Italian architect who has transferred his activity to the Chinese capital. "In recent years, however, the opposite has been happening. The few hutongs that have survived are viewed as sacred relics of the past and as such cannot be touched." Hutong is a typically Beijing term for the narrow alleyways lined by low-rise houses built around traditional courtyards, but by extension has come to refer to the neighbourhood as a whole. Those situated around the Forbidden City are in an excellent state of repair and much sought after by the city's middle class: meticulously constructed grey stone houses, with tiled pitched roof and from which trees emerge suggesting lush courtyards hidden away inside. The more outlying hutongs are quite different. Their small courtyards, originally designed for a single family, are now home to six, because rents are high (around 2,000 euros a month) and this has resulted in overcrowding and inadequate sanitary conditions. But now that the State has taken on the task of protecting the city's heritage, there has been a whole host of ideas on how to make these districts more liveable without altering them or triggering a process of gentrification. In the Baitasi hutong, two young talented architects called Dong Gong and Xu TianTian Hua Li have recently started restoring houses and revitalizing streets and wider sections of road with the participation of local residents (coordination is by the Italian Beatrice. Leanza, creative director of the Baitasi Remade programme). There is also much activity in the Dashilar hutong, situated within walking distance of Tienanmen Square. This is the site for two projects by Zhang Ke, the architect who founded the Standard Architecture studio in Beijing - and both are discussed in this issue of Abitare. The first is a micro-hostel that provides space for four homes, a living-room and even a bathroom (something that can never to be taken for granted in Beijing, where shared facilities are still commonplace) with just 30 square metres to play with. The street gives access to the living area, which looks out onto a tiny courtyard that is extremely picturesque as a result of the building's design: a "cascade" of five concrete cubes vertically connected by simple rung ladders. The second is a crèche, created inside a house that, before becoming the home of a dozen families, was a Buddhist temple. Its courtyard is a riot of accretions and small volumes containing kitchens (one per family). Here, Zhang decided to maintain the add-on elements as a tribute to the past and as a testament to the stratified way in which living is organised in the hutongs, introducing a number of, ultra-designed wooden "boxes" that contain a children's library (measuring nine square metres) and an art workshop (just six square metres). At the centre of the courtyard, around the ash tree that had been almost completely swallowed up by the many additions is a brick staircase that serves as a podium for classes and contains another tiny utility space for the children. This is a delicate and poetic design project that deservedly won the 2016 Aga Khan Award.

Beijing La poesia degli hutong

Nella capitale cinese si moltiplicano le iniziative per far rivivere i quartieri storici dalle tipiche case basse a corte. Ecco due tra gli interventi più interessanti. Firmati da Zhang Ke

Conservare, valorizzare, vincolare. Dopo anni di frenesia edilizia che hanno portato alla demolizione di gran parte dei quartieri storici intorno alla Città Proibita, Beijing ha invertito la rotta. Una frenata brusca che ha dato il via a una nuova linea altrettanto drastica. «Un tempo compariva su un muro un cartello, partivano le ruspe e giù tutto il quartiere per lasciare spazio a nuove torri», spiega Nicola Saladino, un architetto italiano che ha spostato la sua attività nella capitale cinese. «Da qualche anno accade il contrario. I pochi hutong sopravvissuti sono considerati reliquie. Sono letteralmente intoccabili». Gli hutong, termine tipicamente pechinese, sono gli stretti vicoli su cui affacciano le case basse a corte tradizionali, ma per estensione ormai si chiama così l'intero quartiere. Quelli situati intorno alla Città Proibita sono in ottime condizioni e super ambìti dalla borghesia cittadina: costruzioni molto curate, di pietra grigia, con tetto spiovente coperto da coppi, da cui spuntano alberi che lasciano immaginare patii rigogliosi e protetti. Diversa è la situazione degli hutong più periferici. Nelle piccole corti pensate in origine per un'unica famiglia allargata oggi vivono in media sei nuclei perché l'affitto è alto (circa duemila euro al mese), con conseguente sovraffollamento e condizioni igieniche precarie. Ma ora che lo Stato si è convertito alla tutela del patrimonio storico è tutto un fiorire di idee su come migliorare la vivibilità di questi quartieri senza snaturarli ed evitando la gentrification. Nell'hutong Baitasi si sono cimentati di recente giovani architetti di talento come Dong Gong, Xu TianTian e Hua Li, con restauri di case e rivitalizzazioni di strade e slarghi in cui sono stati coinvolti anche gli abitanti (il coordinamento è dell'italiana Beatrice Leanza, creative director del programma Baitasi Remade). Anche l'hutong Dashilar - a un chilometro da piazza Tienanmen - è in fermento. Si trovano qui i due progetti che pubblichiamo in queste pagine firmati da Zhang Ke, architetto fondatore dello studio pechinese Standardarchitecture. Il primo è un micro-ostello che in soli 30 metri quadrati riesce a offrire quattro alloggi, un living e un bagno (mai scontato a Beijing, dove a tutt'oggi negli hutong i servizi sono collettivi). Dalla strada l'accesso è al living, che affaccia su una corte piccolissima ma molto scenografica per come è stato pensato l'edificio: una “cascata” di 5 cubi di cemento collegati tra loro in verticale con delle semplici scale a pioli. Il secondo invece è un asilo ricavato in una casa che prima di alloggiare una dozzina di famiglie era stata un tempio buddista, e in cui la corte era letteralmente invasa da superfetazioni e piccoli volumi che ospitavano le cucine (una per famiglia). Qui Zhang ha deciso di mantenere le addizioni come memoria critica e testimonianza delle stratificazioni dell'abitare negli hutong, inserendovi delle disegnatissime “scatole” di legno che contengono una biblioteca per i piccoli (nove metri quadrati) e un laboratorio per l'arte (sei metri quadrati). Al centro della corte, intorno al frassino che era stato quasi fagocitato dalle tante addizioni, ora si sviluppa una scala di mattoni che serve da podio per le lezioni e racchiude un altro minuscolo utile spazio al servizio dei bambini. Un progetto delicato e poetico che non a casa si è aggiudicato l'Aga Khan Award 2016.