派镇码头

01 December 2009

Fiction

The Whart

Zhu Wen

Gongbu - the south-eastern kingdom that Buddhist master Padmasambhava called the Capital of the Dead - refuses to celebrate New Year on the same day as the rest of Tibet. In Gongbu, it falls on the first day of the tenth month of the Tibetan calendar, for reasons that drift back 700 years, to the reign of King Ajiejiebu. The people of Gongbu say - they've always said - that although King Niechi gave them their independence, it's the heroic Ajiejicbu they should thank for their courage. One year, as deep autumn turned to winter, Ajiejiebu called every fighting man together, to meet an invading army that had broken in through the region's northern rim. But thoughts of the fat pork and barley wine of New Year had driven all the fighting spirit out of the braves of Gongbu. So Ajiejiebu decided to shift the New Yezt to the first day of the tenth month. Their celebrations completed, the merry men of Gongbu marched fearlessly off to rout their enemy in battle. But it was in the last campaign of the war, legend goes, that Ajiejiebu was killed, and his head and limbs hacked from his body. As they marched home, the sons of Gongbu carried aloft the dismembered torso of their leader, their songs of victory saddened by funeral bugles.

Even though the Gongbu New Year was still three weeks away, Gesang wanted to be home, back in Changdu, where his wife and the new-born son he'd never seen were waiting for him. He'd tried asking for leave, but his travel company - a Lhasa-based outfit that managed the boat-trips up and down the Tsampo River - wouldn't let him go. Around twenty years old and new to the job, Gesang was sole caretaker at the wharf that served Pai, the final stop for tourists along the Tsampo River and the jumping-off point for visitors to Tsampo Gorge. By the last month or two of the lunar year, tourists were pretty thin on the ground, but still Gesang had to keep an eye on things. If he left, there would be no-one else to look after the place. He understood this, and it was worrying him.

After breakfast, four ageing backpackers who'd arrived the evening before took up their bags, bade Gesang farewell, and set off towards Motuo. The wharf fell quiet again. Gesang carried the pot of noodles the travellers had only half-finished outside, slopped the leftovers into a trough, then made a loud gurgling call. The pig showed no interest in appearing.

"Little bastard." Gesang's face wrinkled with anxiety.

Something else occurred to him. Still carrying the dripping bowl, he headed for the guest rooms. The inner Flank of the building - behind the waiting room that overlooked the river - was divided into three dormitories laid out with beds for travcllers who had missed their crossing; the last of these had, for the time being, been colonised by Gesang. With far more violence than was necessarr, he shoved the door to the middle room open, the wood jarring against the wall. Only one of the room's four beds was taken - the one furthest from the door. Its motionless occupant, curled up into a ball under his quilt, his coat spread over the top, faced the wall. Gesang briskly, noisily remade the bed nearest the doorway; still his guest failed to move.

"Are you leaving today?" Gesang asked.

"No," the man replied, his left hand emerging to tug the coat over his head.

"When,then?"

"That's my business."

"It's mine too!" Gesang almost shouted.

There was no response.

"Would you mind telling me where you're headed?" Gesang tried a slightly milder approach.

Still no answer. Eventually, Gcsang stormed off, leaving the door open. He shouldn't have let the man stay. Not that it had really been up to him. Ten days ago, the visitor had stepped off the boat along with a tour group of old Chinese cadres, and failed to move on. He'd brought nothing with him except an expensive-looking leather briefcase that he carried over his shoulder. His face had a sick, sad pallor to it. Though Gesang found it hard to age Chinese people, he put this one around forty. He seemed to know his way around the wharf, though: he had made straight for the dormitories. Even then, there was something about him that had made Gcsang faintly uneasy.

'Why don't you stay in Pai?" Gesang had blurted out. He had a point, though. The wharf was quite a distance from the town it served; it was too isolated, too desolate, especially at night, while Pai - set within the region of Nyingchi - had become much more tourist-friendly in recent years. Most visitors either went back to Bayi, or on to Pai. The Chinese man glanced expressionlessly back at Gesang, who now wondered what the hell he was trying to do, driving business away.

"It's forty yuan a night -payment in advance."

After a slight hesitation, the man drew a wad of notes from his pocket, handed four of them to Gesang then turned away again. Examining them, Gesang saw that they were each a hundred yuan.

"How long are you planning to stay?" he asked, now bewildered.

"Don't know." The man didn't even look back.

The wharf was screened, almost secretively, by thtee stout ancient trees, each of whose trunks it would have taken four or five arm-spans to encircle. Its back wall seemed to merge into the cliffs that rose up behind it, and had it not been for the landing stages, approaching passengers might have missed it altogether, mistaking it for a stone cave perched amid the branches. The quay only became conspicuous when tourist boats - stridently announced by their steam whistles - came into dock. Once onshore, visitors followed a roughly paved road up from the river until the building at last emerged before thcm: the waiting room to the right, an underused dining room to the left, the two rooms divided by a stone ramp that led up to the mountains behind. Once you finally had it in your sights, it looked out of place, out of time, perhaps due to its size or dcsign - as if it really shouldn't have been there. It seemed wrong for a wilderness - it looked more like a dacha, a country getaway. Any life to the place was only temporary. Once the travellers had scattered and the boats cast off, the wharf would disappear back into stillness.

Since his arrival - apart from an initial foray into Pai, to buy food and drink - the Chinese man had spent every day inside at the wharf. Gesang couldn't understand why he slept so much during the day: what kind of tourist never went out? Whenever a boat steamed up, he would retreat to his own room and shut the door. He seemed to be waiting for someonc; or perhaps not. Apart from the occasional Tibetan, from one of the handful of villages that lined the Tsampo Gorge, most passengers were tourists. And for three days, no boat had come. Since it had rained during the nights, the days should have been crisply bright. Instead, they had dawned chillingly overcast, with the sun only sttuggling hazily into view at around ten in the morning.

Perhaps drawn out by this weak sunshine, the man clambered up the stone ramp to the railed terrzce that looked out over the river from the roof of the wharf, his thinness and pallor underscored by the daylight. He panted for oxygen through his brief excursion, looking anxiously about him as he walked. By the time he reached the deserted terrace, a thick blanket of cloud had greyed the sky again. He staggered at a sudden gust of wind off the river; a mass of shrivelled yellow leaves scatered off the tree that clung to the roof. Leaning forward, he reached out for the low iron railings, to steady himself, but the frozen metal quickly forced hint to let go. Although it was early winter, the thickly forested mountains on both sides of the river were still sharp with green; the water was murky by comparison.

He watched the river course eastward. Two, maybe three kilometres away, Tsampo Gorge stared straight back at him; as if he could reach out and touch it. Just before the river swelled out into a vast lake, a strange solitary little island squatted in the centre of the narrow mouth to the gorge: the Island of Demons - locals called it the Castle of Luosha, one of the great demons of Indian mythology. When Padmasambhava first reached these parts, he had defcated the local demons led by the King of Gongbu only by winning over the kingdom's Guardian Spirit, Gongzundemu, whom he ordered to hold this island, as a fastness against evil. The faint outlines of a building were just visible: a small temple to the Spirit. Further on lay Namcha Barwa, the easternmost anchor of the Himalayas, its pinnacle obscured by the wreath of cloud that hung about it all year long. As if disappointed to be denied a clear sighting, the man closed his eyes.

A line of white prayer-flags rose up from the gorge's steep right-hand bank, making - as legend told it - the nine turrets of the royal castle of Gongbu. The Chinese man stared out over the stone ruins, his clothes fluttering like the prayer-flags in the wind.

My lover made

For the prayer-flags

On the mountains of Beila

May the wind carry my prayers there too.

A gurgling call interrupted his thoughts: Gesang, charging along the dirt road up to town. Frozen, bewildered, the man set off back down the ramp, his coat wrapped tightly around him. Gesang didn't even notice him - he had thoughts only for his pig.

The Zangxiang pig - with its sharp trotters and spindly tail - is a breed indigenous only to Tibet. They're mostly reted free-range, allowed to wander all over the mountains, their flesh sweetened by the spring water they drink and soft, fine carpets of catetpillar fungus they nibble. A great favourite with tourists, their price had rocketed over the past few years. Since a full-grown specimen would fetch three or four thousand yuan, and even a piglet could go for four hundred, raising them had swiftly become the locals' second most profitable sideline, after (now illegal) logging. Gesang's first idea had been to keep a mastiff, for company in the deserted wharf. But there was no money to be made out of a mastiff. So he settled on a pig instcad: for social and financial reasons. Because his salary was modest, he decided to start off with just one and see how much money he could make out of it when it grew to full size. That was the plan.

His first pig swiftly disappeared into someone else's herd. The loss sharpened him up: why, he berated himself, hadn't he left a mark on it? The moment he got back with pig number two, he gave it a full coat of Propaganda Red - the angry scarlet paint the Party used for sloganeering around the countryside. He rejoiced in the knowledge that his was the reddest pig in Tibet: it could run away to China and he'd still be able to pick it out. Ten days later, the animal was shot dead on the hills by a local hunter, who'd mistaken it for something else - he'd never seen a pig like it in his forty yeas. For a brief while, though, a happy ending seemed in sight. The huntsman kept six pigs - even the smallest of which was much fatter than Gesang's - and offered one as compensation. But before Gesang could congratulate himself on his unexpected good fortune, the hunter produced a wooden truncheon, broke the pig's front leg and handed it over. Too embarrassed to object, Gesang carried the animal, squealing with agony, back home. For days, Gesang hardly slept, as the pig's clies of grief echoed over the river. Thanks to Gesang's ministrations, the leg mended almost perfectly. But then something new began to trouble Gesang: the pig's left buttock still bore the brand of its original owner. How could he prove it was his, and not someone else's? The problem cost him another sleepless night. Early the next day, a solution finally came to him. while the pig was at the trough, snuffling through some barley mush, he snipped off the pig's inconsequential tail with a pair of scissors. Crazy with pain, the pig danced up and down the quayside, trailing blood behind it. Still holding the scissors, Gesang stated curiously down at the tail on the ground, kicking it back and forth. At last, Gesang thought, the world will know that mine is the pig without a tail. As this thought occurred to him, the traumatised, tailless pig galloped up the slope to the termce, took off through the railings and fell to its death on the paving stones below. When Gesang rushed over, the rims of its eyes - fixed gently ahead -were sputteting blood. His was indeed the pig without a tail, but not for long.

The whole business affected Gesang badly. After six pig-free months, though, a chance encounter with a piebald piglet at a farmers' market brought about a change of heart. The animal had not only the same gentle eyes as the second pig, but also the same lack of tail, It had been born like that, its owner told him. Gesang knew instantly that this was the reincarnation of his last pig. It was destiny: he had to have it. But as something still tugged him back from a decision, his mobile rang - it was his wife, telling him she'd had a baby boy. His eyes hot with tears, Gesang scooped up the pig and hurried off home with it.

And it was this reincarnation that Gesang was now searching for. Back and fotth he walked along the dirt road to town, shouting himself hoarse, asking everyone he met: "Seen a pig without a tail?"

Gesang couldn't understand why so many people laughed. By evening, Gesang gave up all hope and despondently headed home. But just before a roadside cairn, he pulled up disbelievingly. A pig was spread-eagled, flat as a flayed pelt, over the soft, wet road. Faint wheel matks over its spine betrayed the work of a lumbering timber truck. In death, as in life, the pig's blank eyes stared gently ahead. His knees weakening, Gesang sank to the ground, scrabbling to unearth the pig's bloody, fleshy buttocks. It had no tail.

He could not understand why pig-keeping was so hard for him, and so easy for others; why life was so unfair. Fury clutched at his young Gongbu heart. His next piglet, he vowed, would live. But fot now, his capital had run out.

A faindy hysterical Gesang rushed back to the wharf, searching everywhere for the Chinese man, as if hc were the murderer of his beloved pig. He had to blame someone - anyone; and the Chinese man was the only available scapegoat. Gesang fiercely kicked open the door to the guest room. The briefcase was lying on the bed, its owner nowhere to be seen. Gesang swung the bag against the wall, listening hopefully for the sound of something breaking inside. Quickly bored with punishing inanimate objects, he threw the bag down and rushed back out. As he didn't know the man's name, he just ran up and down the quayside, hollering. Luckily, the man failed to appear, and after a, few laps Gesang began to tire, to calm down. It was nothing to do with the Chinese man. Gesang now imagined how the last but one pig must have felt, when its tail had just been snipped off. He was suddenly jolted by the conviction that his pig was somehow still alive.

But as soon as Gesang saw the man again that evening, he felt his anger return. The visitor was sitting in the dining room, tending the fire, staring out of the window at the Tsampo River at dusk. The whole thing seemed completely unreal to Gesang. An exhausting mass of doubts and suspicions gnawed at him, How had the Chinese man got in here? The room hadn't been opened for ages. The fireplace had never been used since the wharf opened - it was usually piled with random junk. Gesang had barely even noticed it: how had the Chinese man known it was there? Where had he got the firewood from? Who'd said he could light a fire? Gesang wanted to do a great many things: to ask him all this, to shout at him, to throw him out of the window, to kick him into the river. Eventually, he compressed all his rage into z single accusadon: "You owe me rent."

Which was not untrue. Ten days had passed; more money was due. The man - staring, spellbound, across the rivet at a mist of sand blowing over the bank - finally woke to Gesang's presence behind him. He turned slowly to look at Gesang, a litde puzzled at the fury in his voice. To avoid meeting the man's eyes, Gesang gazed at the fireplace: it was a curious European design he'd never seen before. Slowly drawing from his pocket the wad of notes, the man handed another four hundred over. Although the pinewood fire was cracking and spitting with heat, his hands trembled violently. Gesang wanted, more than anything, to smash this quivering four hundred yuan back in his face. He didn't want his money, he wanted to tell him, he wanted him to get lost so he could go home for New Year. But how could Gesang refuse another four hundred yuan? He could buy a piglet with that. After a brief hesitation, he snatched the money and pedantically counted the four notes.

"You were never here!" He suddenly glared at his visitor.

What did he mean? Don't tell anyone you were here, perhaps; I want to kep this money for myself. The man stared blankly back at him then nodded mechanically, without asking for further clarification. As soon as he'd left the room, Gesang gave the base of the wall a violent kick. He hated himself for not having screamed at his Chinese visitor. And now he'd kicked the wall too hard; his heart ached with the pain in his right foot. Gesang limped off, remembering his pig. It was still alive; he knew it.

Zhaxi reached the wharf at five in the morning. After knocking on every door and window in the building, he eventually roused Gesang, who poked his head out of the door, still half-asleep and wrapped in his quilt. Dawn was a little way off still and the mist outside the door had not yet cleared. His visitor, he saw, was draped in a black wool gown, with a bone-handled dagger at the waist, leading a black horse. Gesang slammed the door so fast he almost trapped his hand. He must be dreaming still, about the ghost of the King of Gongbu coming for him, to punish him for what he'd done. "Don't take me away!" he sobbed.

Four words from his visitor dispelled the pall of the supernatural: "I've got the pig."

Embarrassed, Gesang quickly tugged on his clothes and opened the door, smiling as hard as he could. Gesang had first met Zhaxi - who lived in Zhibai, one of the nearby villages - when the old man had wanted to pair him up with his granddaughter, Zhuoma. She was very pretty and had a beautiful singing voice, but there was a small white cataract in her left eye that had made Gesang uneasy. See that cloud in the sky? the old man asked him. It's like having one of them in your eye. Gesang nodded, still unsure. Fortunately, he was already promised to someone in his own village, the woman who was now his wife; otherwise he would have drifted anxiously into it. Today, though, Zhaxi was here on other business. Gesang had asked him to source him another piglet; this time, he'd emphasised, he wanted a girl.

"Much easier to find a boy," Zhaxi had objected.

"It has to be a girl."

Gesang's pig-rearing failures had made him superstitious: perhaps trying the female of the species would change his luck. Zhaxi untied the piglet hanging upside down by its hindlegs from his saddle and set it down next to Gesang. Tethered by a metre of rope, the piglet staggered woozily about, dazed by its bumpy journey. Gesang squatted down, patiently waiting for it to come round. Zhaxi lit his pipe, blowing a thick blanket of smoke over the animal's snout. To Gesang's partial relief, it snorted groggily. Zhaxi asked Gesang what his plans were: if he wasn't going home, he ought to spend New Year at Zhibai. But Gesang didn't want to risk it, as he'd heard that Zhuoma was still unmarried. He stroked the piglet's fine tail, as he made his excuses. But as he reached, almost without thinking, between the piglet's hindlegs, he suddenly whipped back his hand. "It's a boy!" "Impossible," Zhaxi said, keeping on with his pipe. Gesang turned the pig on its back and splayed its hindlegs in Zhaxi's direction. Now that dawn had broken, Zhaxi had a clear view. Almost dropping his pipe in surprise, he came over and rammed his nose in the pig's groin. "How the hell did that happen?" Zhaxi muttered to himself, vexed by the pig's sudden sex change, tugging the penis back and forth with his stubby index finger, as if wanting to pull the thing out.

"I won't take it." Gesang stood up, shaking his head. Scowling, Zhaxi said nothing. The two men faced each other.

Gesang gave the pig an impatient kick on the buttocks; no response. He gave it a second kick: a bit harder this time, a bit angrier. Male and barely alive, this pig - in Gesang's eyes - was highly defcctive. At this moment, something seemed to snap in Zhaxi. Whipping the dagger from his waist, he threw away the scabbard and yanked the piglet's legs apart.

"What the hell are-" Gesang scteeched.

An instant later, the penis was gone. With a honk of pain, the piglet shot up out of its stupor and stared about in wild confusion. When it finally worked out what had happened, the poor animal tried to charge off, squealing with horror. Zhaxi quickly grabbed hold of the halter, hanging on while the piglet ran bloody circles around him. At this point, the black horse also took fright and stampeded. Though Zhaxi yelled at Gesang to stop it, the young man stood paralysed with shock, both legs jammed together. Fortunately, the horse chose a dead-end; when it came back in the opposite direction, Gesang could seize its reins. Horse and pig now ran laps around the two men.

"Happy now?" Zhaxi shouted at Gesang, as both struggled to restrain the animals.

"It'still not a girl!"

"I did you a favour, cutting that thing off !"

"Why don't you cut your own off, then?"

The horse calmed down first. Eventually, the black pig did too and lay on the ground, as if paralysed. The two men threw down their ropes, and stood there, panting. There was an angry pallor to Zhaxi's face. Gesang didn't dare look up at him: he knew he shouldn't have said what he'd just said. He could only hope the old man hadn't heard him. Quiet returned to the wharf, disturbed only by the groans of the pig.

A man approached, silent as a shadow. The Chinese man. Whercver he'd been, he looked exhausted. His lips were a ghostly white, his empty eyes framed by wildly dishevelled hair. When he passed wordlessly between Gesang and Zhaxi, as if he hadn't even seen them, Gesang could feel the bone-piercing coldncss of him. The man went in through the waiting room and disappeared into the darkness inside. Gesang stared vacantly after him.

"Poisoned," Zhaxi observed.

"What?"

Gesang glanced doubtfully at the old man. Zhaxi motioned inside with his chin. Gesang felt every hair on his head stand up, his spine skittering with shivers. He was starting to understand.

He liked the evenings here: so quiet you could hear your own heart beat. He could imagine he was almost floating along on the river: his body warming, as if he was returning to the womb. When he woke in the night, he had given up trying to work out whether he was conscious or dreaming. He had abandoned all consciousness of time, all need to wake at prescribed times -it was wonderful.

He sat up, pulled on his coat, then got up and slowly pulled on his trousers and shoes. He hated shoes with laces and trousers with button flies. Every outline in the room was clear, as if it had been washed by moonlight. Onc step after another took him towards the door; but as soon as he had gone out, he hesitated: should he take his mobile phoncs? Go on then, a voice told him. One step after another took him back into the room. He groped around his bed until he found his bag. But there seemed to be something wrong with the phones when he found them. He tipped the bag's contents onto the bed. Both his phones were in pieces: seeen, battery, cover. Though he tried to reassemble them, he couldn't quite do it, because they were different makes. He started to sweat with anxiety, his fingers began to disobey him. Why couldn't he do something so simple? He was about to cry with the frustration of it.

Eventually, irritation woke him. He looked about him, then out of the window. He must have been dreaming, he thought. As soon as he saw the pile of mobile parts on the bed, he felt unsure again.

Going out for a, second time, he approached Gesang's room, pressed his ear to the door, and heard a regular snore. He gently pushed on the door: it was bolted from inside. He now plodded back to his own room and sat on the bed, fighting the desire to go to sleep. Something was making him uneasy.

The cold woke him the second time. He was now surrounded by crumbling, overgrown ruins. The darkness had slightly greyed; cloud hung thickly in the distance. Where was he? It was familiar, but also strange - as if he was in a waking dream. Scrambling to his feet, he looked around. To his left a narrow flight of stone stairs led up to a bare, tamped earth wall festooned with white prayer flags. He decided to climb up to see what lay beyond. With each step that he took, a great river extended before him. His eyes smarted with the familiarity of it - he sensed he was about to wake up. He accelerated until suddenly he almost stepped out into a void: when he looked down, he discovered he was standing on the edge of a precipice - one more step and he would have fallen to his death. He cried out with fear - he couldn't stop himself - but the sound was swallowed up by the canyon.

Now fully conscious, he recognised the ruins of the castle of the Kings of Gongbu. His gaze swept the landscape before him, searching for the wharf. In the darkness before dawn, all he could see was the Tsampo rushing into the gorge; the wharf would be in that final bend of the river. He noticed that the black writing on the fluttering ptayer-flags had smudged. He closed his eyes, as if waiting for the wind to blow him off balance.

Black, ink on white cloth,

Blurred after the rain.

However hard l try,

My feelings can never be unwritten.

By the time he got back to the wharf, day had properly broken. He could hardly believe he had walked so far. He was almost delirious with exhaustion: unsure whether he was dreaming or actually seeing the things he passed. Just as his craving for a bed had become almost unbearable, the wharf appeared before him, with a black horse and a black pig running circuits around two men. This - he had no doubt - was a hallucination.

How could he have been so careless, Gesang belaboured himself: he'd almost let this Chinese man die in front of him. As he had no idea how much trouble the whole thing might bring to his door, the more he thought about it, the more afraid he became. Poisoning your enemies had a venerable pedigree in Gongbu. When he was small, Gesang had seen an old poison-woman dragged through the streets after she'd been caught, wooden stakes stuck into her fingers. Usually, you poisoned someone to steal their good luck: you stored the poison in your fingernails then slipped it to your victim when he or she wasn't looking. Once the victim was dead, the theory went, all their blessings would pass to their murderer. Or sometimes, if a man was about to set off on a long journey, his lover would slip poison into his wine. If the man didn't come back when he said he would, he wouldn't get the antidote before the poison started to work. Though Gesang didn't know why the man had been poisoned, he was sure he would die soon. Gesang only hoped he'd hold on until his bosses arrived.

While the Chinese man slept, Gesang spent the day running between the terrace (to see whether any boats had come into view) and the man's room (to check whether he was still breathing). The castrated pig was in even worse shape than Gesang's visitor. Gesang had, in the end, bought it, for a, hundred yuan less than the asking price, firstly because he was sorry he'd shouted at Zhaxi, and secondly because he wanted to thank the old man for having pointed out the poisoning business to him. But he couldn't bring himself to feel any great love for the animal. Gesang had looked out a filthy white hada scarf that a tourist had left behind and bound it clumsily around the piglet's groin to stop the bleeding. He'd then tried to find a suitable hiding place for the animal - he didn't want his bosses to know he was keeping a pig at the wharf. Finally, he tethered it to one corner of the terrace, figuring that they wouldn't go up there because it was too cold. Every time Gesang ran up to the terrace, the pig insisted on snorting at him. Even though Gesang's head was full of the Chinese man, he was still irritated by the fact that the piglet seemed to be deliberately trying to sound like a girl.

"Shut up or I'll poison you!"

Finally, at three p.m., the quiet of the Tsampo River was destroyed. Gesang had never seen anything like it in all his time at the wharf: a triangle of three speedboats trailing behind them six snowy trails of spray. His blood surged with the roaring of the motors. He jogged up to the river's edge and leapt onto the landing stage, waving as hard as he could.

About twenty grim-faced men disembarked. In addition to his travel company boss, the party included representatives from Public Security, Special Services, Public Hygicne, Tourist and Border Defence, as well as local government. A Chinese man had been poisoned in Tibet: this was a serious business, especially after last year's riots. Gesang led the way, listening to the oppressive tread of taskforce feet over the cobbles. His legs almost buckled at every step.

The man was lying motionless on the bed furthest away, facing the wall. When Gesang timidly stepped forward to remove the coat covering the man's head, he felt as if he were lifting a shroud. The corpse suddenly sat bolt up; everyone started with ftight. Looking round, the Chinese man discoveted a dark, dense mass of people crowded around his bedside. A look of intense confusion overcame him, as if he were struggfing to work out whether this was really happening. In the meantime, everyone else in the room inspected him back, trying to assess - from his own angle of expertise - the victim's situation. As the air inside the room seemed to set with the strangeness of it, a plaintive squeal drifted in from outside, a squeal that only Gesang could identify.

After this had gone on some time, an overweight man shoved his way up to the bed through the crowd. "Dr Zhang!" He began pumping the Chinese man's hand. "What are you doing here? Did you come all the way from Beijing?" After a second, the Chinese man recognised his interlocutor. "Who...?" He motioned around at everyone else in the room. "This is Dr Zhang, the great architect!" the overweight man explained to everyone else, in some over-excitement. "He designed the wharf." No-one seemed particularly cheered by this news. Not only had a Chinese man been poisoned; he was also one of the great architects of Tibetan development. It was all so much worse than they had first feared. Now it was the turn of a Public Sccurity man with burning eyes to approach Dr Zhang's bedisde. "When," he wanted to know, "did you discover you'd been poisoned?" Bemusement flickered back onto the great architect's face. "Poisoned?" he mumbled, frowning "I just wanted to come back here for a look - I've wanted to for years. But there never seemed to be time. Until now. So I just decided to come - I didn't want to put you to any trouble, that's why I didn't tell anyone. What's all this about poison?" Every gaze now swept onto Gesang. The suddenness of it paralysed him - as if he had been nailed to the ground. A second plaintive squeal floated into the room, a squeal that once more only Gesang could identify.

As far as Gesang was concerned, everything that happened next was a nightmare. Each dignitary personally, individually took responsibility for swearing at him. Because they were each of them so very eminent, and were from different departments, no-one wanted simply to replicate any of the lectures that had already been delivered - that would have been far too facile, too unimaginative. So they pushed their creativity to its limits, searching for inventive new ways to humiliate him. Eventually, Gesang burst into tears: not because of all the shouting, but because so much of it was incomprehensible to him. "He's Tibetan," someone finally whispered, "best lay off." The special taskforce withdrew, their suits rustling.

Only the corpulent director of the travel agency remained, instructed by his bosses to look after the architect. Dr Zhang reatised he couldn't stay on here any longer, and decided to go back to Beijing the next day. The director was brimful of suggestions for the architect's last night, but evety one of them was refused: he just wanted to stay at the wharf he had designed. Like a good host, the director had to bumout his guest, and contented himself by organising a farewell banquet. His savaging at an end, Gesang now spent the rest of the day fetching and carrying between Pai and the wharf. He couldn't understand why he, who wanted to go home, couldn't, while the Chinese man, who didn't want to go home, could. After all the trouble his visitor had caused him, Gesang now had to go and get him barley wine. The very thought of it made Gesang want to poison it - not so as to kill him, just to give his stomach a good turn. As night gathered in, the director, along with a few government officials from Pai, set raucously to feasting the architect in the dining room. While Gesang was struggling to work out how to keep the fire going - it was different from the charcoal braziers he was used to - his boss (who had drunk himself into a good mood) suddenly called him over to drink a toast a penalty. "He," he slurred to the architect, pointing at Gesang, "was the one who said you'd been poisoned." He had been poisoned, the architect spoke up for Gesang. So was everyone who came to this part of the country: they either couldn't leave, or were always wanting to come back. What a way with words Dr Zhang had, everyone agreed.

Holding a bowl of barley wine aloft, Gesang's face was flushed with discomfort. Hoping to put Gesang at his ease, the architect got up to clink bowls with him. "I was never here," he said, with a wink. Gesang's head went blank with shock - he didn't realise it was a joke. What would happen to him if all these men from the government found out what he'd done? As Gesang was about to gulp the wine down, his boss stopped him. "Don't be such a savage. Come on, sing us a drinking song first!" Gesang's head remained blank. "I don't know any," he mumbled. The director wasn't having any of it: A Tibetan not know any drinking songs? Impossible! Sing! When Gesang insisted that he really didn' t know any, the director stated swearing at him again, this time drunkenly. "Forget it," the architect cut in. "He doesn't know any." Still the director wouldn't give up. "Just sing anything, any Tibetan hunting song. How about 'Good Luck', or 'The Golden Mountain of Beijing'? You must know 'The Golden Mountain'." Realising he didn't have a choice, Gesng sang it through in Tibetan. He felt he sang badly - as if someone had him by the throat as he croaked his way through it - but his audience applauded him enthusiastically. At last, the architect and Gesang could drink their wine, while the fat director recovered his good spirits and rewarded Gesang with a hunk of yak meat and a bear-hug. "Not a patch on Zhuoma, of course," he said. "But she's a girl," Gesang shyly objected. "l can't sing high like she can." "What are you talking about?" his boss argued back, staring hard at him. "Bet you'd sing higher than her if I chopped your balls off." The whole room roared with laughter. Gesang's Chinese wasn't quite good enough to catch what the director said, but he joined in anyway.

The architect tossed and turned, thinking of his journey back tomorrow. His reassembled mobile phones lay by his pillow. After a final hesitation, he turned them back on. In seconds, they began generating messages.

He thought back to the day that he had left Beijing. Because of a project in Shenzhen, he'd practicalty been living at the office for the best part of a week and had fallen asleep, exhausted, on the sofa. At five that morning, he had sat up, suddenly convinced he was about to miss a plane. Picking up his briefcase, he staggered out of the door and grabbed a taxi to take him to the airport, urging the driver to hurry. Finally, in the empty departure lounge, he woke up from his dream. He was seized by depression: not because of the sleep-walking - that had happened to him before - but because he realised he would have to go back to work. After a cup of coffee in the Starbucks at the airport, he had an idea: why not carry on with the dream? As if he'd never woken up. He had taken both mobile phones out and turned them off.

Two hours later, he lay on his bed, all the phone calls he needed to make out of the way; at last he felt sleepy. He thought vaguely of tomorrow: about the director coming over first thing, along with some vice-president from somewhere else. There would be no more opportunity to explore, to say goodbye to the gotge. Regret prickled him. Then he fell asleep.

It was a full moon. The still air felt moister than it did during the day, as if touched by the warmth of a spring night. He climbed slowly up the ramp, looking anxiously about as he walked. At last, he stood to one side of the terrace. The Tsampo River hung in the air before him, like a great, long snake of silver-white silk. By night, it seemed to have a soft suppleness that it lacked during the days.

He stood there, staring out into the canyon. He shut his oxygen-starved eyes, taking greedy gulps of air, thinking about the river coursing into the canyon - a long antenna exploring the world's last perfect wilderness, hemmed in by the gorge. A curious, long lost sense of excitement seized hold of him and his hand slipped inside his trousers. Waves of pleasure, mimicking the pull of the river, rippled through him, as his breathing grew laboured, his body hotter. At the point of ejaculation, Namcha Barwa suddenly emerged from deep within the gorge, pulling clear of the clouds that usually surrounded its summit - he was sure of it. For the briefest of instants, the happiness was too much for him. He lay down.

Despite the short notice, the director had prepared vast numbers of local specialities for the architect to take back with him to Beijing. Bag after bag of them Gesang had had to drag onto the motorboat. But he didn't mind: because he thought once he'd got rid of his unwanted visitors, he could go home. Last to embark was his boss, whom Gesang carefully helped onboard. This was his last chance, he thought.

"Would it be all right, sir, if I went home now?"

But the director suddenly remembered a piece of turquoise sent by the mayor that he'd left in the waiting room. Gesang ran back to get it. He couldn't believe his eyes: it was an enormous, uncut slab of stone, weighing at least fifty kilograms. By the time Gesang had hauled it over to the boat, he was too out of breath to say or do anything, except stand on the landing stage, watching the boat swagger off upriver.

When he had recovered, Gesang thought it was time to go and deal with the pig. He'd changed his mind: he'd decided to slaughter it. Pigs were there to be killed and caten, as well as reared. There was still some barley wine leftover from yesterday. Thinking he'd celebrate New Year early, he began to cheer up.

But only an empty tether and a wind-dried blood stain remained where he'd tied it yesterday. His transsexual pig had disappeared. This time, Gesang didn't bother looking for it. He squatted down on the terrace and realised he wasn't cut out for this life. Why should he run around after other people all the time? Why couldn't he go home to spend New Year with his wife and son? So he left. He nevcr came back.

The pig was cold, hungry and had lost a dangerous amount of blood. Around midnight, as it was nearing death, someone or something trod on its thin tail; though its impulse was to recoil, it was too weak to move. A little later, a few drops of hot liquid fell into its open mouth. Gulping them down, it managed to struggle to its feet, licked the rest of the warm stuff from the ground, then lay down again. At four or five in the morning, the pig stood up, as if in a dream, and easily - the noose had grown too big fat its undernourished neck - slipped out of its tether. On trembling legs, it walked down the ramp from the terrace, and along the side of the wharf, resting evety few paces against the wall, as if checking it was going the right way. Halfway down the stone path to the riverside, it gave up and rolled a while, then stood up and crawled on, until it could move no more and a rush of warmth suddenly bore it aloft.

As if dead to the world, it bobbed along in the river, until eventually its head collided with a rock. The pig now woke, unable to understand what it was doing in the water. As it did not, of course, want to drown, it began struggling towards a bank. Once on dry land, it shook the drops of water off its body and looked around. It had no idea where it was.

Two or three hours later, when the sun rose, the pig finally understood that it had become the sole resident of Demons' Islalnd.

After a long, hard winter, during which the pig somehow survived by eating everything that could be eaten on the island, it was discovered by a devout local come to burn incense for Gongbu's Guardian Spirit and was acclaimed a Holy Pig. From this point on, it grew to be the happiest, fattest pig in Tibet, feasting on offerings, worshipped by multitudes. Its clumsily foreshortened penis only heightened its cult.

The Holy Pig of Demon Island drew waves of curious tourists, until this once-quiet wharf dcveloped into a busding port. When the sun was out, the pig would stand on its island, looking magisterially out, watching the Tsampo River roll towards it, convinced that it was its Guardian Spirit.

And so it was that the world's last perfect wilderness was destroyed by a pig.

Information

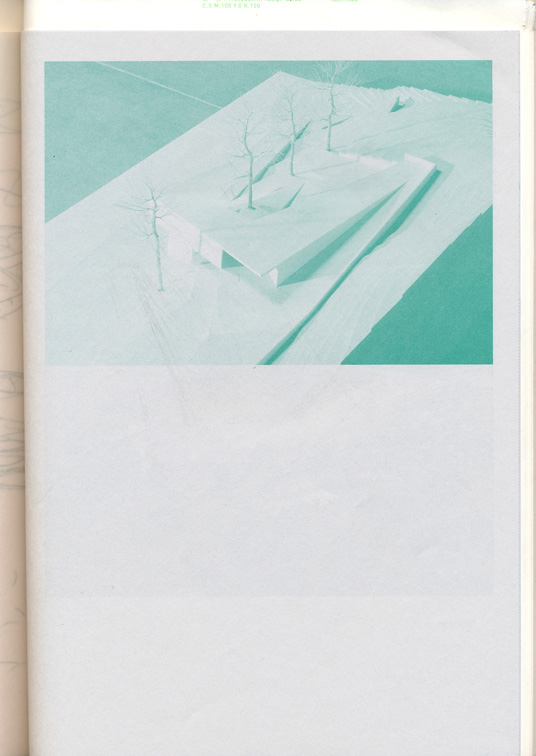

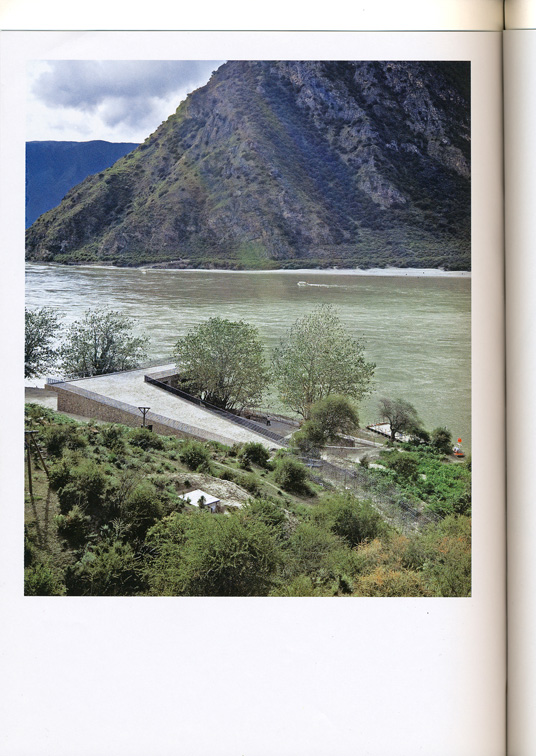

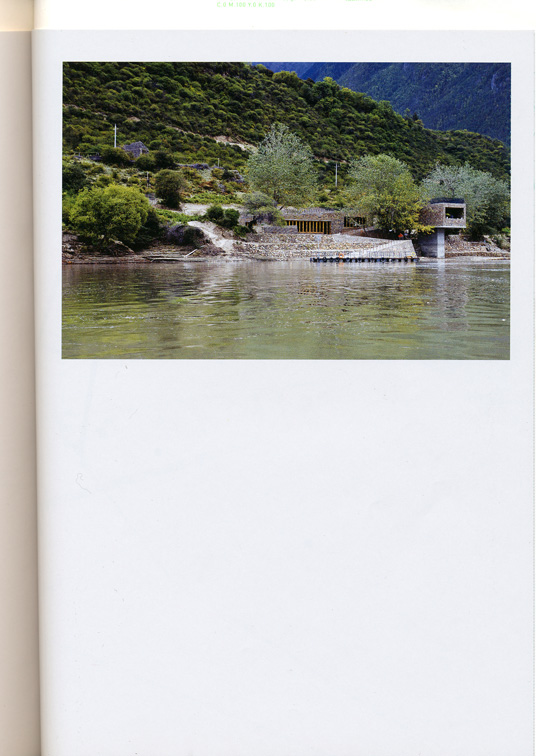

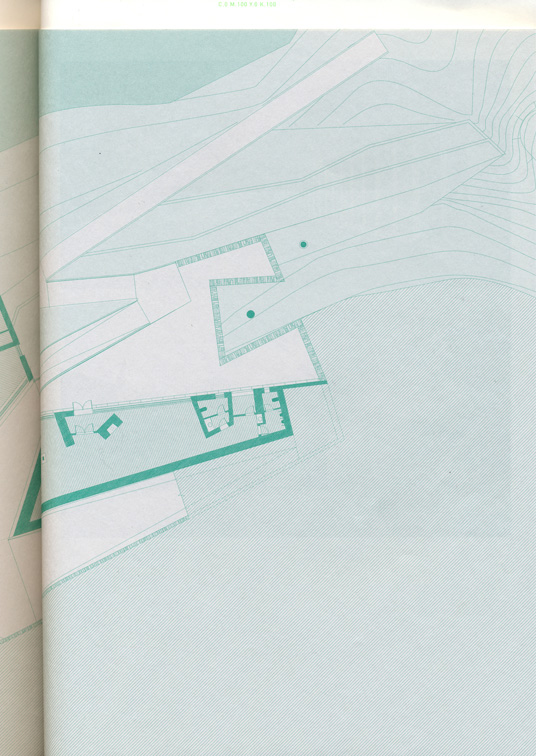

Project Name:Tibet Yaluntzangpu Boat Terminal

Location:Linzhi, Xizang

Date:2008

Phase:Complete

Use of the Building:Public

Site Area:1000 m²

Gross Area:430 m²

Client:Tibet Tourism Holdings

Name of Architects:Hou Zhenghua, Zhang Ke, Zhang Hong, Claudia Taborda, Dong Lina, Sun Wei, Sun Qingfeng

Structure:Concrete Frame

Principal Exterior Material:Stone Masonary

Principal Interior Material:Woods, Stone Masonary

Landscaping:Standard Architecture

Interior:Standard Architecture

Other Consultants:China Academy of Building Research

General Consultants:Tibet YouDao Architecture Design Co., Ltd, Tibet Hengxin Construction Co., Ltd.

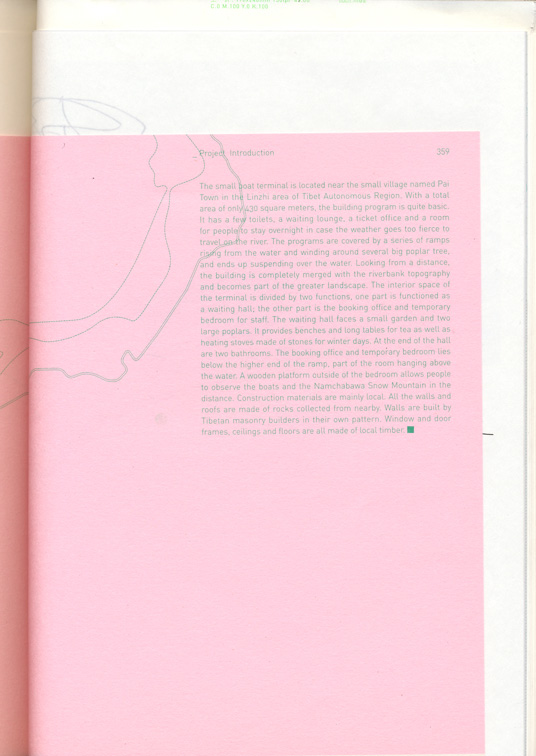

Project Introduction

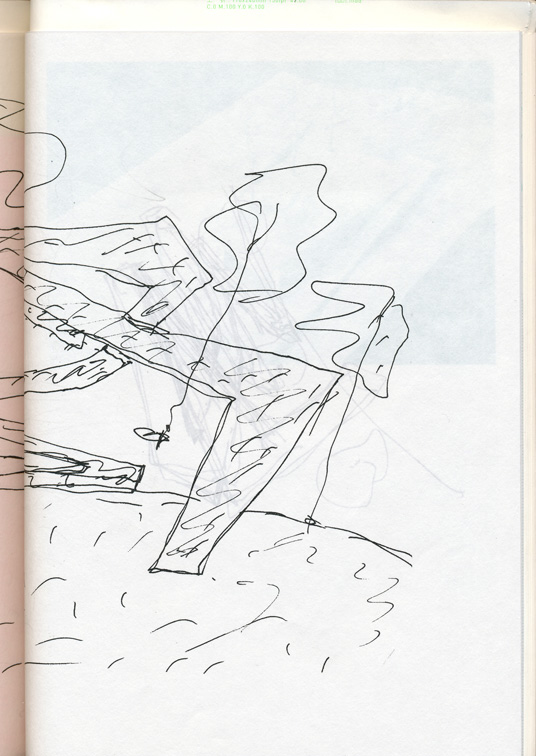

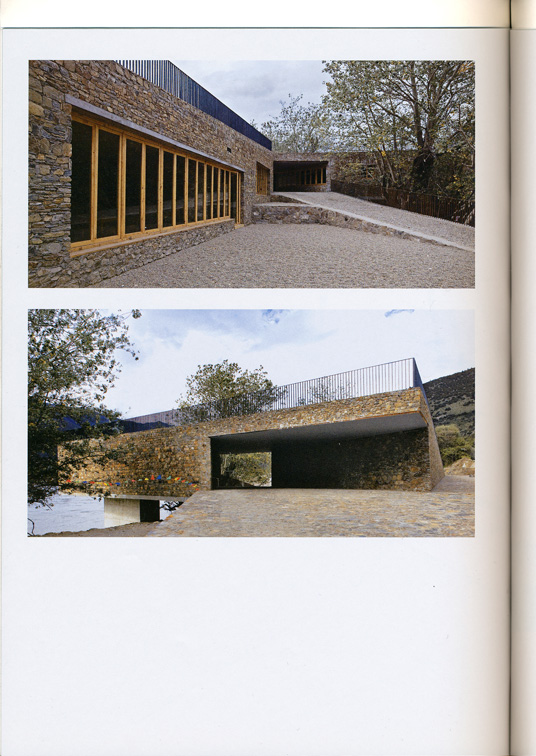

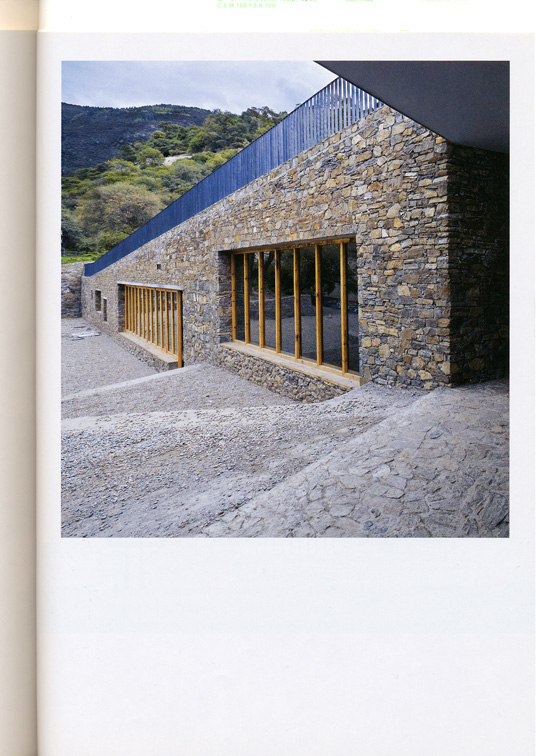

The small boat terminal is located near the small village named Pai Town in the Linzhi area of Tibet Autonomous Region. With a total area of only 430 square meters, the building program is quite basic. It has a few toilets, a waiting lounge, a ticket office and a room for people to stay overnight in case the weather goes too fierce to travel on the river. The programs are covered by a series of ramps rising from the water and winding around several big poplar tree, and ends up suspending over the water. Looking from a distance, the building is completely merged with the riverbank topography and becomes part of the greater landscape. The interior space of the terminal is divided by two functions, one part is functioned as a waiting hall; the other part is the booking office and temporary bedroom for staff. The waiting hall faces a small garden and two large poplars. It provides benches and long tables for tea as well as heating stoves made of stones for winter days. At the end of the hall are two bathrooms. The booking office and temporary bedroom lies below the higher end of the ramp, part of the room hanging above the water. A wooden platform outside of the bedroom allows people to observe the boats and the Namchabawa Snow Mountain in the distance. Construction materials are mainly local. All the walls and roofs are made of rocks collected from nearby. Walls are built by Tibetan masonry builders in their own pattern. Window and door frames, ceilings and floors are all made of local timber.

小说

派镇码头

朱文

随着他一步一步地接近土墙,一条气势雄伟的大江跃现在他的面前,他惊愕不已,熟悉的感觉铺天盖地向他袭来,让他热泪盈眶,他觉得自己已经到了临近梦醒的最后时刻。

壹

和西藏其他地区不一样,工布是在藏历十月一日过年,究其原因就要说到七百多年前的工布王阿杰结布。工布地区被称为“死者的都城”,这一说法在莲花生大师五部遗教之《神鬼遗教》中就有记载。工布人有句话世代相传:聂赤成就了工布的独立,而阿杰结布给工布人带来了勇敢和自信。阿杰结布是最受尊敬的一代土王,在他的统治下工布部落昌盛无比。当时有一支强大的外敌进犯北部边境,阿杰结布要率领部落所有的男人离开家乡去迎战。正值深秋初冬,年关将近,工布汉子们想到过年的青稞酒和肥猪肉就全身懒洋洋的,斗志全无。阿杰结布看在眼里,当即决定把新年提前到十月初一。工布汉子们过完年心里痛快,没有牵挂,打起仗来个个卖命,最后当然把敌人给打跑了。但是据说也就是在这次战争的最后一次战役中,阿杰结布不幸牺牲,被敌人砍掉了头颅和四肢。工布子民扛着他们首领残剩的躯干,吹着悲怆的号角,胜利凯旋了。

离工布新年还有二十多天,格桑就待不住了。他刚工作不久,二十出头,家在昌都,老婆和刚出生还没有见过面的儿子正盼着他回去呢。他想请假,但是领导不批准。他工作所在的派镇码头,上属拉萨一家负责雅鲁藏布江旅游开发的上市公司。派镇位于雅鲁藏布江中下游,是雅江旅游的终点,也是著名的雅鲁藏布大峡谷的起点,行政属于现在的林芝。而林芝就是工布的中心。虽说进入阳历十一月以来,游客已相当稀少,但是整个派镇码头也就格桑一人照看,他如果走了,码头怎么办呢?格桑心里也清楚,所以他着急。

早饭以后,四个昨晚到达的老驴友背着行囊向格桑告别,动身前往墨脱。码头一下子安静了下来,格桑端着旅客吃剩的半盆面条来到屋外,把它倒到了猪食槽里,然后嘴里“咕噜噜咕噜噜”地唤着。猪始终没有出现。格桑脸上渐渐有了不安之色。

“该死。”他骂了一句。格桑忽然想起了什么,手里提溜着还滴着汤水的空盆直奔客房。在候船厅的里侧备有三间简易的客房,供错过船班的旅客过夜。最外边的那间权且被当作格桑的宿舍。他推开最里边的那间,用力过猛,木门磕在墙上发出“哐”的一声。房间里并排放着四张铺,只有最靠里的那张铺躺着人。那个人面朝墙壁躺着,一动不动,整个人蜷缩成一团,外衣盖在被窝上。格桑故意整理了一下门口那张铺,动作很响,但是那个人还是一动不动。

“今天走不走?”格桑问到。

“不走。”那个人回答得很平静,从被窝里伸出左手把外衣往上拉了拉。

“那你什么时候走?”格桑继续问到。

“那是我的事。”

“也是我的事!”格桑几乎喊了起来。

那个人不予理睬。

“能告诉我准备去哪吗?”格桑用稍微平缓一点的语气又问了一句。

对方还是没有回答。格桑戳在那里等了一会儿,然后生气地一跺脚走开了,任凭房门敞着。现在他很后悔当初同意那个汉人住下。其实也没有同意不同意这回事,十天前那个汉人和一个内地的老干部旅游团乘同一班船来到这里,然后就这么住下了。他没有什么行李,单肩挎着一个薄薄的、做工非常精细的皮质公文包,面色苍白,神情忧郁。格桑看汉人不准,估计他有四十多岁。这个汉人似乎对码头不陌生,径直往客房方向过去。格桑当时就觉得什么地方有点不对劲。

“你可以住在镇上。”格桑脱口而出。他说的也是实话,派镇码头离派镇还有相当一段距离,过于孤立、冷清,尤其在夜里。而派镇这些年因为搞旅游,生活条件有所改善,要方便许多。一般游客要么回八一住,要么就住在镇上。

那个汉人站了下来,回头看了一眼格桑,脸上没有表情。后者顿时觉得自己好没道理,哪有放着生意不做的。

“40 块钱一张铺,先交钱。”

那个汉人迟疑了一下,从口袋里摸出一叠钱,数出四张交到格桑手里。格桑接过来一看,不是四十而是四百,有点懵。

“你这是住几天?”格桑对着他的背影问了一句。

“再说。”那个汉人头也不回。

贰

在三棵四五个人方可合抱的古树掩映下,派镇码头显得相当隐秘。石头的外墙使整个建筑与它所背靠的山崖融为一体,如果不是江边趸船的提示,你也许会忽略它的存在。从江面向上仰望,你会误以为树冠之中似乎有一眼石窟。只有当客船进浦时,随着汽笛的轰鸣,整个码头的轮廓才会突然显现出来。上岸以后,顺着错落有致的石子路上行,如同进入一个简朴的园林,整个建筑真正向你徐徐展开,右首是候船厅,左首是茶室,中间是通透的长廊对着色彩斑斓的山坡。不管是规模还是风格,都与所处的环境极不相称,有一种时空错位的感觉。它不像是一个蛮荒之地的小码头,而更像是一座避世独居的大别墅。

热闹是短暂的,当旅客散去客船开走,码头仿佛又会在寂静中一点一点地隐去。那个汉人几乎整天待在码头,除了刚来的那天去了趟镇上,拎了一大袋吃喝的回来,就没再出去过。格桑不明白他为什么喜欢白天睡觉,一个游客白天不出去转,还叫什么游客。每次有船来的时候,他都会回到自己的房间,把门关上。他似乎在等什么人,似乎又不是。乘船往来的大部分是游客,少数是当地人,藏族、门巴族、珞巴族都有,属于峡谷边上的几个村庄。已经连续三天没有船来了。夜里下过一阵雨,白天应该非常晴朗才对,但是没有,一直阴着,气温偏低,到上午十点多钟的时候,好不容易才出了一阵太阳。

也许就是因为这一阵太阳,那个汉人出来了,顺着一侧的斜坡走向码头屋顶的露台。在阳光下他显得更为苍白、憔悴,这么短的路他都走得吃力,边喘着气边有些着急地扭头向东边张望。当他终于来到露台上时,太阳却再次被厚厚的云层所遮蔽,天彻底暗了下来。露台相当宽敞,空荡荡的,一阵江风来得突然,几乎使他站立不稳。紧贴着露台的那棵古树飘下一大阵脆黄的落叶,撒了一地。他连忙下意识地俯身抓住有些低矮的护栏,但护栏是铁的,透凉,他又不得不松开手,但身体还保持着前倾。虽然已是初冬,两岸却青山如黛,层林尽染,江水少有的清澈。

他顺着奔腾的江水向东边放眼望去。大约两三公里以外,雅鲁藏布大峡谷的峡口正对着他,仿佛触手可及。过了狭窄的峡口,江面忽然变得开阔起来,形成了一个偌大的圆形湖泊。而就在峡口的正中央,孤零零地蹲踞着一座怪异的小岛。这就是“魔鬼岛”,当地人叫它“森不藏”,意思是罗刹城堡。莲花生大师到此传教时与当地的群魔有过激烈的争斗,那是佛苯相争时期,工布王也被看作恶魔之主。为了永久地镇住魔鬼,莲花生大师收服了工布原先的保护神工尊德姆,令她镇守此岛。岛上隐约可见一座房子,那就是工尊德姆的小庙。再往纵深方向,就应该是南迦巴瓦了。这座神秘的雪峰终年云雾缭绕,难得一见尊容。他似乎有些失望,闭上眼睛,休息了片刻。

峡口右侧陡峭的江岸上插着一大排白色的经幡,那里就是传说中工布王九个尖顶的城堡所在,如今只剩一片废墟。那个汉人对着那片废墟看了很久,他的衣角也像经幡一样在风中瑟瑟发抖。

白布的经幡

高插在北拉的山头

我的情人走向哪方

风啊,望你也把幡儿吹向哪方吧!

这时,身后一阵“咕噜噜咕噜噜”的叫声把他唤醒。格桑正心急火燎地奔走在江边那条通往派镇的土路上,他一边走,一边大声唤着。那个汉人回头不解地看了看格桑,他觉得浑身凉透了,把外衣裹裹紧,动身往下走。而格桑并没有注意到屋顶上那个孤独的汉人,因为此刻他的心里只有猪。

叁

格桑养了一只藏香猪。藏香猪是高原独有的猪种,尖蹄、细尾巴,生得十分乖巧。一般都是放养,满山遍野地乱跑,喝的是山泉水,吃的是松茸虫草,所以肉质极为鲜美。来藏地的游客都对它垂涎三尺,藏香猪的价格因此一路飙升。一只大的藏香猪最多可以卖到三四千块钱,连猪苗都可以卖上四百,养殖藏香猪迅速成为当地人第二大方便的经济收入。第一大方便的是乱砍乱伐,卖木材,已被政府明令禁止。格桑原想养只獒,因为码头这么大就他一人,养只獒可以作伴。但是养獒不能挣钱。所以格桑觉得养猪是最好了,既可以做伴,又可以挣钱。他工资有限,没有多余的钱,所以只能买一只来养。他希望把这一只养大,然后卖掉,挣它一 笔再说。

他养的第一只藏香猪很快就被别人的猪群带走了。他很后悔没有做记号,亏了钱但长了记性。第二只刚买回来,格桑就从码头库房里找出半罐宣传红把它浑身上下刷成了红色。他想这下好了,全西藏这么红的猪也就一头,就算跑到内地去我也能把它找回来。但是谁又能想到呢,没过十天他的猪就被人一枪打死在了附近山坡上。开枪的是一位门巴族猎人,他活了大半辈子也没见过这样的猪,以为是别的什么动物。好在他讲道理,同意赔偿。猎人家里总共养了六头藏香猪,最小的一只也比格桑原来那只肥多了。格桑正在心中窃喜,谁知猎人抄起一根木棍,二话不说把最小那只猪的前腿给打折了,然后把折了一条腿的猪赔给了格桑。格桑也不好说什么,只好抱着那只嗷嗷惨叫的藏香猪回家。那几天格桑都没有睡好,夜里那只猪凄厉的叫声在江上盘旋,让人毛骨悚然。在格桑的精心照料下,那只猪终于痊愈,甚至那条前腿都不怎么瘸了。但是新的问题又来了,猪的左臀上留有原来主人的记号,是烙铁烫的,怎么都去不掉。怎么能证明这只猪是我的而不是别人家的呢?格桑为此一夜没有合眼。第二天一早他终于想出了办法。格桑趁猪正在槽边吃青稞的时候,飞快地用剪刀一举铰掉了猪的尾巴。藏香猪的尾巴太细了,铰起来是那样的容易。只听一声惨叫,没有尾巴的猪一路滴着血在码头上下没命地乱蹿。格桑手里拿着剪刀,盯着那条刚被铰下的猪尾巴在地上一个劲地蹦,觉得非常新奇。格桑想这下好了,没有尾巴的猪就是我格桑的。他正想到这里,那只没尾巴的猪顺着那条斜坡一路狂奔上了露台,腾空而起,越过了护栏,最后“嘭”地一声摔死在一块石板上,肝脑涂地。当格桑赶过去时,它的眼眶还在汩汩地往外冒血,而眼睛一直瞪着,眼神是那样的温柔。没错,没有尾巴的猪是格桑的,只是属于他的时间太短了。

这件事让格桑深受刺激,很长时间没有心思再养猪,直到半年后,他在八一农贸集市意外地与藏香猪前缘再续。他没法不把它抱回去,因为那只黑白杂毛的猪苗不但有着一样温柔的眼神,而且也一样没有多余的尾巴。据卖猪的人说,这只小猪天生就没有尾巴。格桑觉得这简直就是上一头猪的转世,他没法不养它。但是还是犹豫,这时他的手机响了,是他老婆打来的,告诉他孩子出生了,是个儿子。格桑满含热泪地抱起那头小猪扭头就跑。

现在格桑正在四处寻找的就是这只转世的、没有尾巴的藏香猪。他已经在江边的那条土路上来回了十几趟,喉咙都喊哑了。他一路寻到了镇上,逢人就问。

“你见过一只没有尾巴的猪吗?”

格桑不明白这样严肃的问题为什么总是让人发笑。到傍晚格桑觉得没希望了,只能往回走。他一路低着头,失魂落魄。当走到玛尼堆附近时,格桑忽然站住了。他简直不敢相信自己的眼睛,一只猪背朝上匍匐着,被完整地嵌入了雨后松软的路面,平展得像一张毛皮。毛皮上隐约有着轮胎的痕迹,一定是那种运木材的大车干的。那双猪眼直愣愣地瞪着他,眼神依然温柔,格桑只觉得膝下一软,跪了下来,用十指从土里抠出那个血肉模糊的后臀,忍不住号啕大哭起来,没有尾巴啊没有尾巴。

他不明白为什么养一只藏香猪会这样的难,而其他人养一只藏香猪为什么又那样的容易,人世间为什么这样不公平。愤怒的情绪紧紧地攫住了一颗工布汉子年轻的心。他咽不下这口气,他赌咒发誓,一定要再养一只猪,而且一定要把它养大!只是他已经拿不出买猪苗的钱了。

肆

有些失去理智的格桑一头冲进码头,四处寻找那个汉人,仿佛他就是压死他那头心爱的藏香猪的凶手。必须要有一个人为此负责,而这个狗屁地方除了那个汉人就没有第二个活人了。格桑猛地踹开客房的门,看到那个汉人的公文包在床上扔着,但是人不在。他操起那个包抡圆了砸在墙上,听到里面有什么东西碎裂的声响。他无暇多管,把包一扔,掉头又冲出门去。不知道那个汉人的名字,他只好一路哎哎哎地乱吼着,屋前屋后一阵乱蹿。幸好那个汉人不在,格桑蹿了几圈以后有点累了,人也平静了一些,这事毕竟跟他无关嘛。格桑觉得刚才的自己就像那只刚被剪掉尾巴的藏香猪,这么想时他忽然感觉到那只猪没死,它还活着,整个人为之精神一振。

当完全平静下来的格桑终于见到那个汉人时,他还是无法做到平静。那个汉人在茶室坐着呢,一边烤着火,一边静静地看着窗外雅鲁藏布江的黄昏。这是格桑从来没有见过的场景,他觉得这一切不可能是真的。

太多的疑问折磨着格桑,让他心力交瘁。这个茶室很长时间没用过了,平常都锁着,他是怎么进去的?码头投运以来茶室的