Urban Agricultural Infrastructure

01 September 2013

Village Mountains

Urban Agricultural Infrastructure

Zhang Ke in Conversation with Cruz Garcia

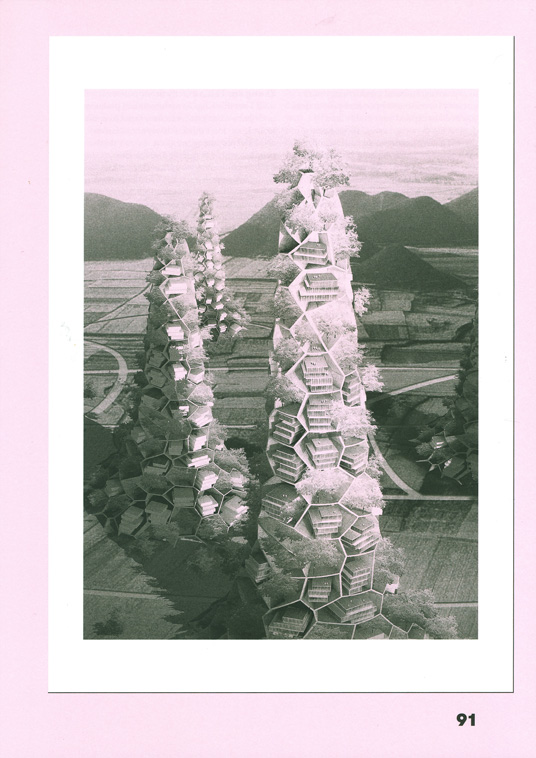

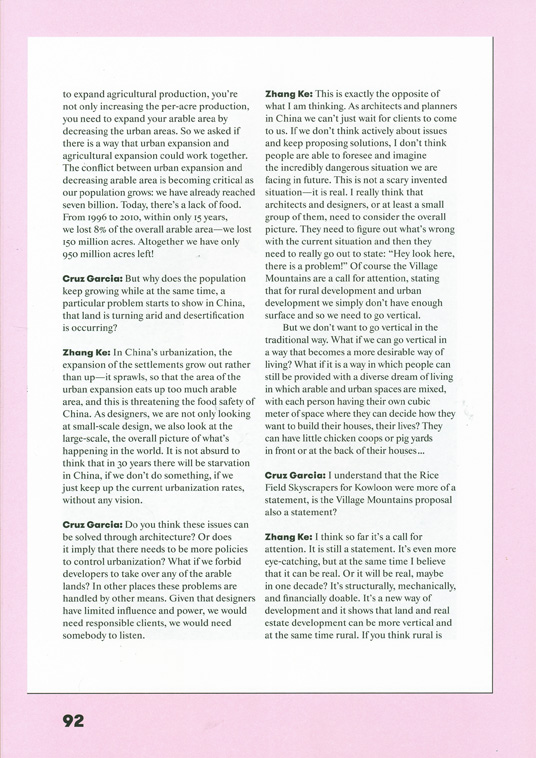

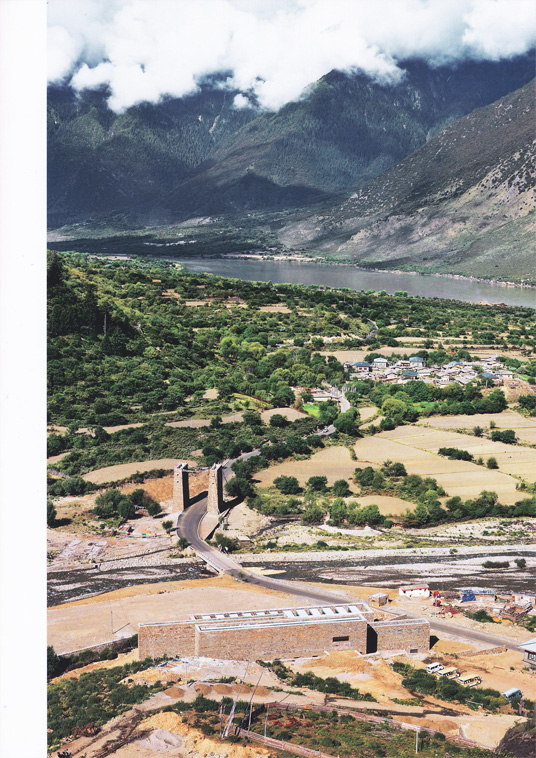

From 2010 to 2015 the hunger for urbanization in China has devoured 12 million acres of land per year and a staggering 150 million acres of arable land were consumed by urban sprawl from 1996 to 2010. Facing these revealing figures and concerned about the struggle of the growing urban area versus the decreasing arable area, standardarchitecture has proposed a solution in the form of a colossal infrastructural hybrid that integrates architecture and urbanism, the countryside and the city.

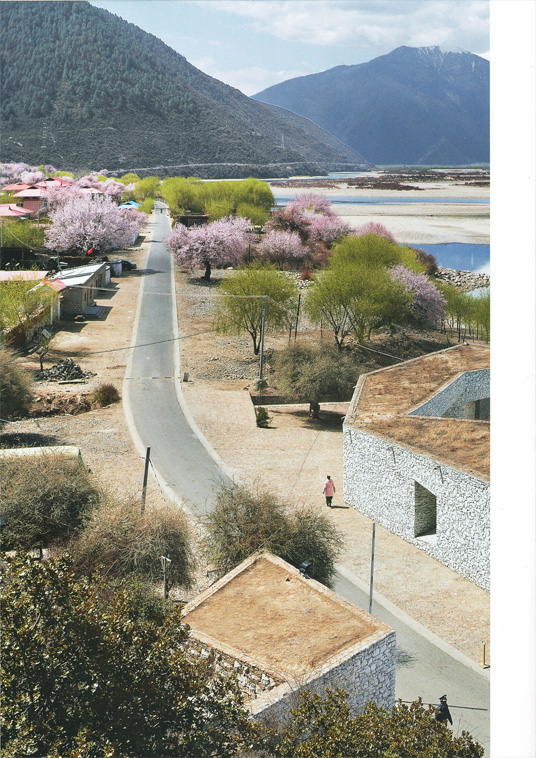

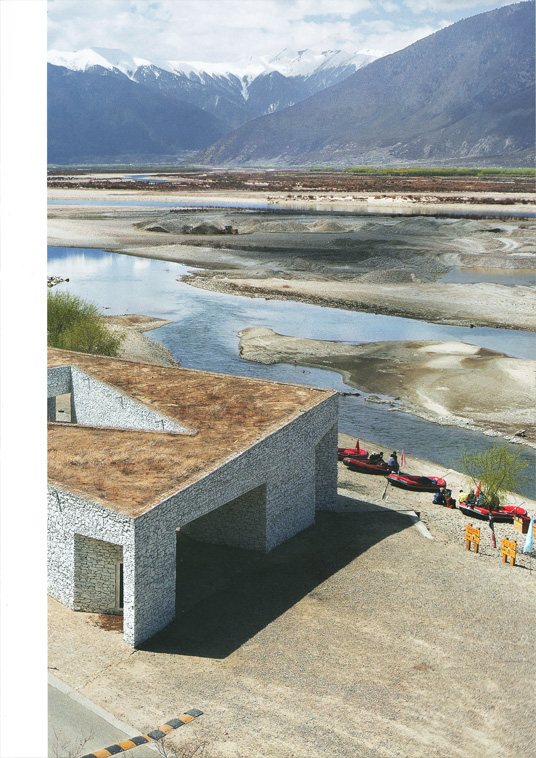

The Village Mountains proposal offers a vision for a new form of urbanism in which arable land and the urban, infrastructure and architecture become one. Cruz Garcia (WAI Think Tank) discusses with standardarchitecture's founding principal Zhang Ke the concepts and theories that drive the Village Mountains proposal and the evolution of his vision for the future of the city.

Cruz Garcia: Could you start by telling us how your interest in the relationship between agriculture, architecture, and the city became manifest in some of your projects? As we have noticed, the Village Mountains seem to be a continuation of a developing concept that dates back to the art project of Un-natural Growth (Formica Art Exhibition) to the project presented at the Hong Kong-Shenzhen Biennale (2007-08) and eventually to the projects you have presented at the Chengdu Biennale (2011) and at the design weeks in Milan and Beijing.

Zhang Ke: At the Hong Kong-Shenzhen Biennale the question of what the rural should be, or could be in the future, was not yet being addressed. Back then, with the West Kowloon Mountains, we were interested in how agriculture could be brought into an urban area, and how agriculture could be a strategy for urbanism.

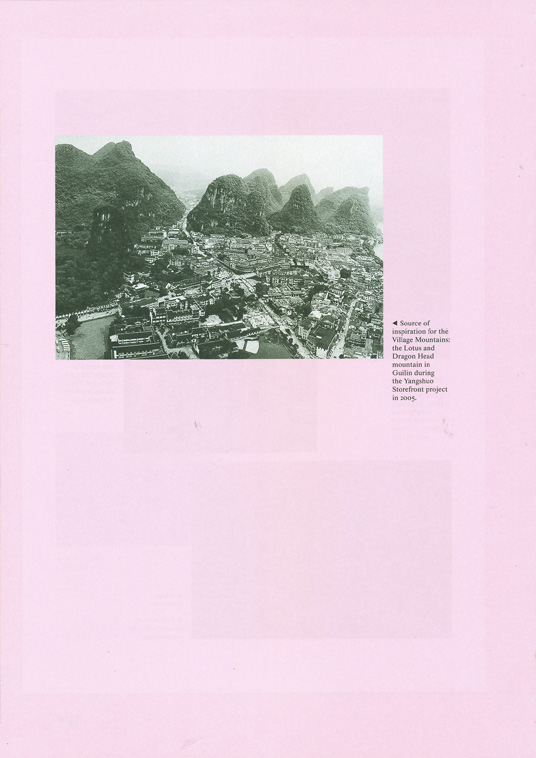

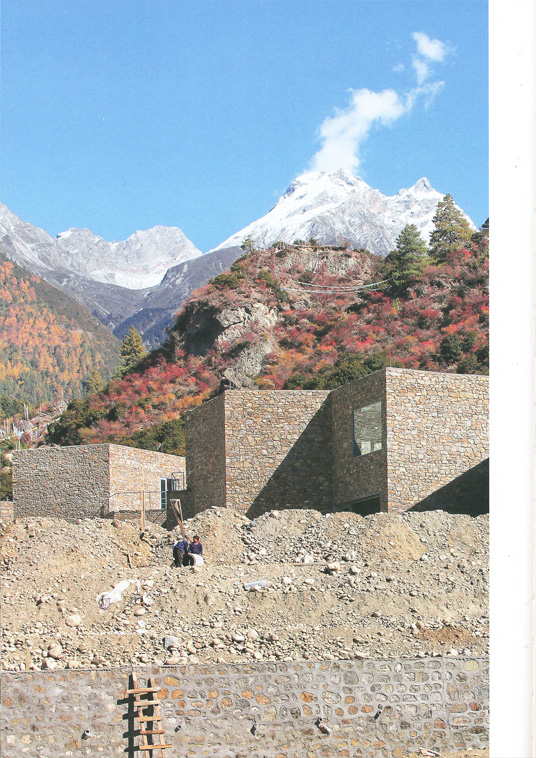

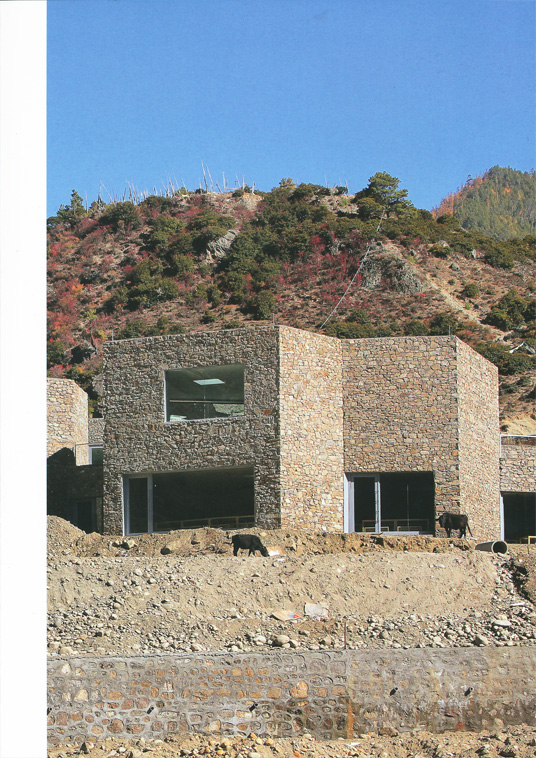

However, before the Biennale we were already working on mixing mountains and agriculture with urbanism during our Yangshuo Storefront project; we built a small storefront among the mountains. I think this was the first time that we were inspired to discover how someone can live around, among, and inside the mountains and how we could merge these findings with our urban imagination. It was the most Chinese land-scape that was the inspiration, the first step-that's how the inspiration came to us.

Cruz Garcia: Although this was the first step, it didn't have form yet. How did the concept evolve from the Yangshuo project to the Un-natural Growth project and the work exhibited in the biennales and design weeks? How did the idea evolve from the inspiring experience of building in such a powerful landscape to the Village Mountains?

Zhang Ke: I would like to elaborate a little bit more about the West Kowloon Mountains project. Of course at that time, in 2007, nobody really talked about agriculture. It was still the peak of a frenzied time. But then when everybody was so infatuated about this crazy thing, it became a matter of gaining even more attention-to make people think and ask: "Does our urbanism have to be in opposition to agriculture? Can they coexist in the same space at the same time?"

Agriculture usually and naturally occupies the outer surfaces of the settled space and urban life occupies most of the inside. And then, of course, there's an overlap. So if you bring agriculture back into the city, in a massive way, as we did when we designed terraced slants with rice fields, which we called Rice Field Skyscrapers, it can bring a completely new urban experience, an almost rural experience which is desperately craved by urban dwellers. Although it was the time of the financial peak, 2007 was also the beginning of the global food shortage. The project became a provocation: we wanted to throw a stone into the water and see the ripple effect. The project was less about a solution, and more about and exploring an idea and making a statement.

Cruz Garcia: The Rice Field Skyscrapers were a statement, not a project? Was that the beginning of your interest in urban infra-structures for agriculture?

Zhang Ke: Not only, it was also a critique of what I thought was wrong with the West Kowloon land reclamation and planning at that time. Of course, Hong Kong is the world's most urbanized place, but why do you build this huge artificial landfill, which took a huge amount of public money? Originally Norman Foster proposed to cover the site with a big shell, which seemed ridiculous in a hot tropical environment, which then led to the idea of a series of buildings-some cultural projects here and there-which seemed like a strategy that was not financially sustainable at all.

So what we were proposing was actually smart. With the budget of a huge landfill we created a mixture with a balanced program. On the one hand we proposed the world's tallest department store for the inside of the skyscraper-which basically is what defines Hong Kong-embedding (like jewels in the mountain) cultural facilities, galleries, and theaters while on the outside of the building, we offered an agricultural urban experience that can be explored by all the citizens of the city-which is what Hong Kong is lacking.

This was the first time we started tackling the relationship between a futuristic human-made infrastructure and an urban infra-structure, in correlation with agriculture.

Cruz Garcia: The Rice Field Skyscrapers raise the provocation: “If you're going to make all this effort to make something absurd, at least make it sustainable?”

Zhang Ke: The funny thing is although most people think it's absurd, it is actually the most needed. So for me it's the least absurd. I don't even think it looked absurd. It's just that nobody really thought of it before. Look at the mountains through the eyes of a child. Children love the idea of the Rice Field Skyscrapers because they don't think it's absurd, they think, "Wow great! We can play on the outside surface of the building!"

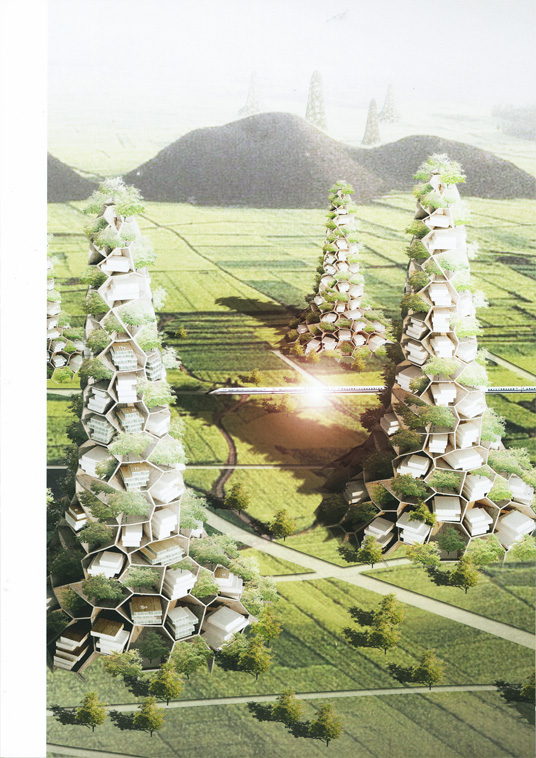

Cruz Garcia: In your Beijing Plan for 2030, the Village Mountains were set into the periphery of Beijing as a new efficient linear center, with a highly efficient mass transport system to free the city center from cars and to leave space for agriculture. This project was based on numbers, discovered during your research. Did the subsequent projects also respond to statistics?

Zhang Ke: When I did the research for the Chengdu Biennale in 2011 I discovered that in China, as everywhere else, urban expansion invades agricultural land. Then, if you want to expand agricultural production, you're not only increasing the per-acre production, you need to expand your arable area by decreasing the urban areas. So we asked if there is a way that urban expansion and agricultural expansion could work together. The conflict between urban expansion and decreasing arable area is becoming critical as our population grows: we have already reached seven billion. Today, there's a lack of food. From 1996 to 2010, within only 15 years, we lost 8% of the overall arable area-we lost 150 million acres. Altogether we have only 950 million acres left!

Cruz Garcia: But why does the population keep growing while at the same time, a particular problem starts to show in China, that land is turning arid and desertification is occurring?

Zhang Ke: In China's urbanization, the expansion of the settlements grow out rather than up-it sprawls, so that the area of the urban expansion eats up too much arable area, and this is threatening the food safety of China. As designers, we are not only looking at small-scale design, we also look at the large-scale, the overall picture of what's happening in the world. It is not absurd to think that in 30 years there will be starvation in China, if we don't do something, if we just keep up the current urbanization rates, without any vision.

Cruz Garcia: Do you think these issues can be solved through architecture? Or does it imply that there needs to be more policies to control urbanization? What if we forbid developers to take over any of the arable lands? In other places these problems are handled by other means. Given that designers have limited influence and power, we would need responsible clients, we would need somebody to listen.

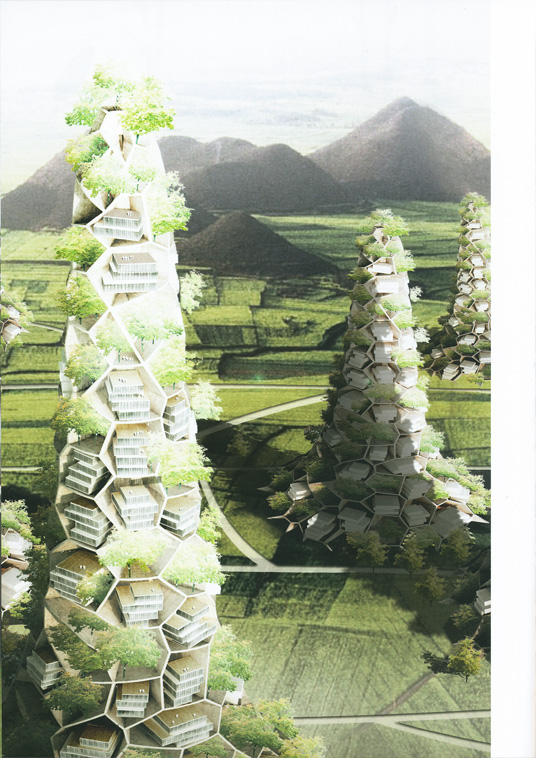

Zhang Ke: This is exactly the opposite of what I am thinking. As architects and planners in China we can't just wait for clients to come to us. If we don't think actively about issues and keep proposing solutions, I don't think people are able to foresee and imagine the incredibly dangerous situation we are facing in future. This is not a scary invented situation-it is real. I really think that architects and designers, or at least a small group of them, need to consider the overall picture. They need to figure out what's wrong with the current situation and then they need to really go out to state: "Hey look here, there is a problem!" Of course the Village Mountains are a call for attention, stating that for rural development and urban development we simply don't have enough surface and so we need to go vertical.

But we don't want to go vertical in the traditional way. What if we can go vertical in a way that becomes a more desirable way of living? What if it is a way in which people can still be provided with a diverse dream of living in which arable and urban spaces are mixed, with each person having their own cubic meter of space where they can decide how they want to build their houses, their lives? They can have little chicken coops or pig yards in front or at the back of their houses...

Cruz Garcia: I understand that the Rice Field Skyscrapers for Kowloon were more of a statement, is the Village Mountains proposal also a statement?

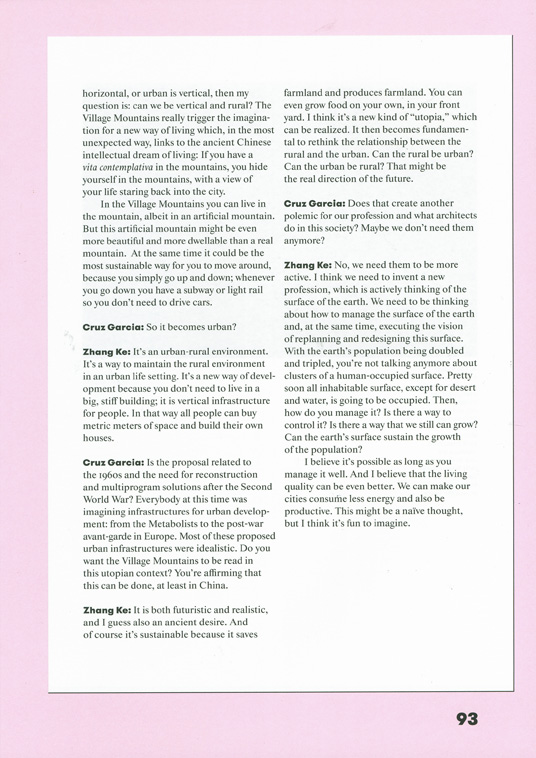

Zhang Ke: I think so far it's a call for attention. It is still a statement. It's even more eye-catching, but at the same time I believe that it can be real. Or it will be real, maybe in one decade? It's structurally, mechanically, and financially doable. It's a new way of development and it shows that land and real estate development can be more vertical and at the same time rural. If you think rural is horizontal, or urban is vertical, then my question is: can we be vertical and rural? The Village Mountains really trigger the imagination for a new way of living which, in the most unexpected way, links to the ancient Chinese intellectual dream of living: If you have a vita contemplativa in the mountains, you hide yourself in the mountains, with a view of your life staring back into the city.

In the Village Mountains you can live in the mountain, albeit in an artificial mountain. But this artificial mountain might be even more beautiful and more dwellable than a real mountain. At the same time it could be the most sustainable way for you to move around, because you simply go up and down; whenever you go down you have a subway or light rail so you don't need to drive cars.

Cruz Garcia: So it becomes urban?

Zhang Ke: It's an urban-rural environment. It's a way to maintain the rural environment in an urban life setting. It's a new way of development because you don't need to live in a big, stiff building; it is vertical infrastructure for people. In that way all people can buy metric meters of space and build their own houses.

Cruz Garcia: Is the proposal related to the 1960s and the need for reconstruction and multiprogram solutions after the Second World War? Everybody at this time was imagining infrastructures for urban development: from the Metabolists to the post-war avant-garde in Europe. Most of these proposed urban infrastructures were idealistic. Do you want the Village Mountains to be read in this utopian context? You're affirming that this can be done, at least in China.

Zhang Ke: It is both futuristic and realistic, and I guess also an ancient desire. And of course it's sustainable because it saves farmland and produces farmland. You can even grow food on your own, in your front yard. I think it's a new kind of "utopia," which can be realized. It then becomes fundamental to rethink the relationship between the rural and the urban. Can the rural be urban? Can the urban be rural? That might be the real direction of the future.

Cruz Garcia: Does that create another polemic for our profession and what architects do in this society? Maybe we don't need them anymore?

Zhang Ke: No, we need them to be more active. I think we need to invent a new profession, which is actively thinking of the surface of the earth. We need to be thinking about how to manage the surface of the earth and, at the same time, executing the vision of replanning and redesigning this surface. With the earth's population being doubled and tripled, you're not talking anymore about clusters of a human-occupied surface. Pretty soon all inhabitable surface, except for desert and water, is going to be occupied. Then, how do you manage it? Is there a way to control it? Is there at way that we still can grow? Can the earth's surface sustain the growth of the population?

I believe it's possible as long as you manage it well. And I believe that the living quality can be even better. We can make our cities consume less energy and also be productive. This might be a naïve thought, but I think it's fun to imagine.